City Plan 2040, adopted by City Council in 2020, recommended a number of general housing policies. These policies resulted from an extensive and robust community engagement program that took place over three years:

- Enable a range of housing types in each part of the community to achieve inclusive, livable neighborhoods that prosper over time. [Livable Built Environment Housing Priority. Policy 3]

- Identify and remove barriers to housing choice. [Interwoven Equity Neighborhood Choice Priority. Policy 3]

- Develop varied and affordable housing options in each neighborhood. [Interwoven Equity Neighborhood Choice Priority. Policy 4]

- Promote complete neighborhoods by allowing a mix of housing types in each neighborhood. [Land Use Complete Neighborhoods Priority. Policy 1]

- Enable affordable and accessible housing options in all neighborhoods. [Livable Built Environment Housing Priority. Policy 1]

- Enforce housing codes to preserve safe and well-maintained housing [Livable Built Environment Housing Priority. Policy 2]

- Understand the connection between finances, housing, and literacy in order to remove barriers for vulnerable people like veterans, homeless people, elderly, domestic violence victims, formerly incarcerated people, and people recovering from addiction [Interwoven Equity policy 2]

- Support the concept of greenlining, or providing special financial resources in neighborhoods that were formerly redlined [Interwoven Equity Priority Policy 3]

- Avoid displacement resulting from gentrification. [Interwoven Equity Policy 5]

- The presence of a large number of people living near neighborhood centers creates a symbiotic relationship. The residents patronize the businesses and the businesses provide convenient access to residents for daily or weekly needs. Population within walking distance is essential to the success of a neighborhood center.

- Households have become much smaller over the past 50-60 years. Housing units increased by 51% between 1960 and 2020, while population increased by only 3%. Average people per housing unit decreased from three people to two. This seemingly small number has a very large impact because of neighborhood scale. A neighborhood with 1,000 housing units in 1960 would house 3,000 people but only 2,000 now. Pre-1950 house forms were built to accommodate large, extended families that are no longer as prevalent.

- Post 1950 housing subdivisions consist of one housing type that doesn’t support all life cycles. These neighborhoods lack options for younger and older families.

- Arguments that affordable housing will reduce property values are not evidence based. Studies over the past 25 years have all but invalidated the idea that construction of affordable housing nearby reduces property values.

- Special exception and rezoning processes have a chilling effect on housing development. The process itself is a barrier and some won’t bother. While nominally permitted, requiring a special exception for certain types of housing prevents those types of housing. Housing development proposals, regardless of their quality, benefit, and consistency with City policy, are often met with strong neighborhood opposition. Recent research suggests that citizen opposition has, in part, led to the national housing shortage (see Neighborhood Defenders 2019).

- Housing studies confirm a general shortage of affordable housing, a situation confirmed by the large amounts of apartment development that recently came online, is under construction, or is planned (over 1,500 units). These developments will likely help with the mismatch of households with units. Still, while far greater production than publicly supported development, the private market’s rates of housing production have been too low to make up the housing deficit.

- Proactive inspections of rental units began in 1997 with the adoption of the Rental Inspection Program. Rental Inspections are limited to geographic areas adopted by City Council based on findings of deterioration. Code of Virginia specifically precludes designation of entire locality as Rental Inspection District. Prior to 1997, there was very little oversight of rental unit conditions prior to the program. Roanoke continues a long recovery from many decades of exploitation and irresponsible property stewardship by a handful of landlords. This legacy has contributed to a persisting bias against rental housing and the families who rent housing.

- The housing of vulnerable populations has historically operated under a policy of concentration and containment. Places for people experiencing homelessness, people fleeing domestic violence, people who were incarcerated, and people who are recovering from substance use disorder are severely limited. Roanoke has traditionally sought severe limitations on this activity through zoning. Result is large scale concentration in a handful of locations. Community conflicts ensue when new housing is requested, even when there is no evidence that neighborhood harm or property devaluation would result.

- Parking inconvenience should never drive housing decisions.

- In community development, there is a complex dilemma: people don’t want their neighborhoods to stay the same or get worse, nor do they want rapidly increasing rents that could displace existing residents. Merriam Webster defines gentrification as the process of displacement of residents that could result when repairing and rebuilding homes and businesses. There is little evidence of significant gentrification in Roanoke. A relatively new measure, called displacement risk, can measure a neighborhood’s relative exposure to gentrification forces. This index has been mapped in larger cities, but has not yet been mapped in Roanoke. Such data could help communities understand if they should be concerned about gentrification or not.

- Roanoke has 28,000 single family properties and each is an opportunity to create an Accessory Dwelling Unit (ADU). This housing type has the potential to provide affordable housing for extended family or small households in every neighborhood.

- Low Income Housing Tax Credits are underused in the Roanoke area.

- Many neighborhoods are eligible for Historic Rehabilitation Tax Credit projects but are not seeing much activity.

- The Greenlining Institute promotes greenlining as a restorative measure to past redlining. Greenlining.org defines greenlining as “the affirmative and proactive practice of providing economic opportunities to communities of color.” While greenlining may not undo all the negative impacts experienced as a result of redlining and systemic racism, it is an equitable approach for moving forward.

- Former places of worship in neighborhoods are opportunities for housing development.

- Low interest loans can enable developers to move a housing development from market rate to affordable.

- Missing Middle housing types fit into neighborhoods and provide a range of housing options. These are house-scaled residences with 2-10 households, townhouses, accessory residences, and small lot, small footprint single household residences. Some of Roanoke’s most successful neighborhoods are filled with exemplary models of Missing Middle housing types that are simply part of the neighborhood fabric.

- Roanoke has an abundance of property in strips and older centers that underused and underdeveloped (grayfields). These properties represent hundreds of acres that could and should be repurposed for residential uses. The land bank could be used to purchase low-performing and unproductive commercial properties for new residential development.

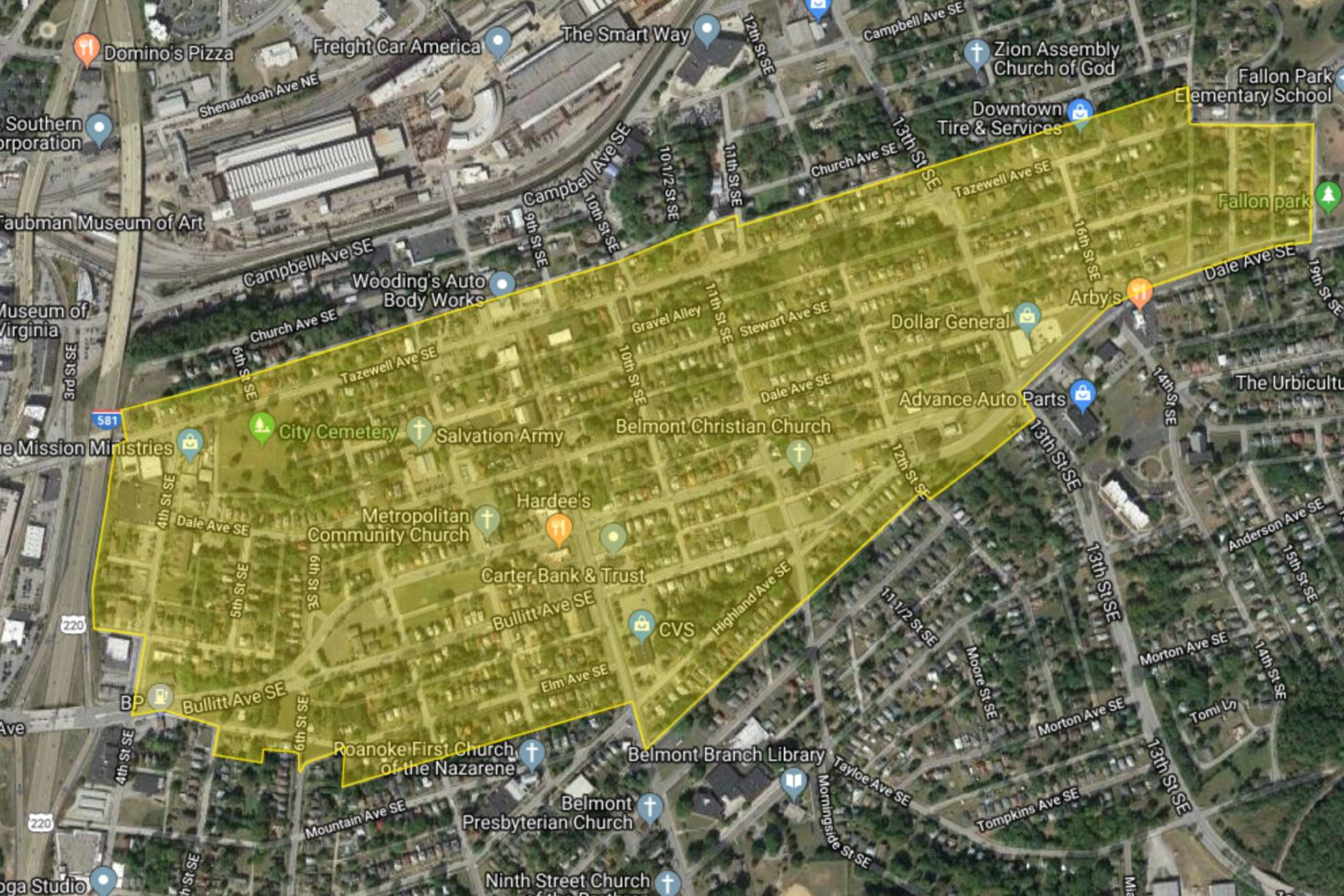

- Residual properties from 10th St NW and 13th St SE street widening projects could support development of well-designed Middle Housing buildings.

- Over time, Roanoke has reduced and then completely eliminated minimum parking requirements, meaning more land can be dedicated to housing.

- HOME ARP funds leveraged with ARPA funds will provide 50+ permanent supportive housing units over the next 5-7 years.

- Utility connections for water and sewer are a serious barrier to new development in places where the sale or rent levels are lower; they constitute a much larger percentage of the development cost.