Interwoven Equity

Vision: In 2040, Roanoke is both a diverse and an inclusive community with access and opportunities available to all including: education, housing, healthcare, employment, and quality of life. Roanoke recognizes how these opportunities are interconnected and how past actions created barriers that limited opportunity for underserved communities, particularly the African-American community, and eroded trust in institutions. To maintain a high level of Interwoven Equity and inclusion, the community is engaged continuously to identify and predict changes that could become opportunities or barriers and to adapt appropriately to those changes.

Defining Equity

Roanoke will not reach its full potential as a community unless each citizen has the opportunity to reach their full potential. Equity involves the fair distribution of investments and services and the removal of institutional or structural policies that can be barriers to success. Equity is the idea that different groups have different needs and should be provided services determined by their needs. If the City gives everyone equal treatment regardless of their individual needs, then it may be unintentionally creating disparate outcomes.

Visualizing Health Equity: One Size Does Not Fit All Infographic by RWJF on RWJF.org

In this plan, the term interwoven equity means that ideas about equity are woven into or embedded within each theme of the plan.

The intent of this plan is to ensure equity in our policies as they relate to race, ethnicity, age, gender, gender identity, disability, sexual orientation, and any other characteristics upon which people are discriminated against, oppressed, or disadvantaged. This plan dedicates most discussion to racial equity because of its profound impact on the physical development of the City.

A History of Inequity

Any conversation on equity must acknowledge racist policies that existed throughout the country and were present here in Roanoke. While openly racist laws may have come and gone, implicit or proxy policies took their place and some have yet to be completely left behind. The consequences of these policies are still felt today, manifested in de facto housing segregation along with persistent disparities in income, education, employment, incarceration rates, community health, and a pronounced wealth gap.

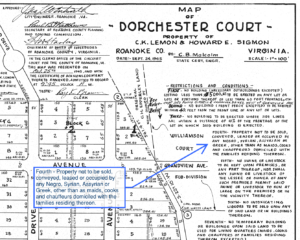

Throughout much of the 20th century, African Americans were subjected to a coordinated effort of government and real estate interests that limited where they could live. Jim Crow laws started spreading through the south just as Roanoke was incorporated in 1882. In 1911, Roanoke adopted residential segregation ordinances that remained in place for years until a 1917 Supreme Court decision declared such laws unconstitutional. Roanoke eventually repealed these ordinances, but private interests continued to enforce segregation effectively through private restrictive covenants in deeds and through redlining. Redlining was the practice of mortgage and mortgage insurance companies that rated neighborhoods based on perceived risk of default. “Hazardous” or “Fourth grade” classifications were given to low income neighborhoods disproportionately occupied by African American families.

These practices, individually and cumulatively, had insidious results. Limiting African American families to a relatively small area of the City and limiting the number of housing units available to them. Segregation induced scarcity which drove up rents for Black residents. For those who could get a mortgage within the redlined areas, the interest rates were much higher. Barriers to home purchase put constraints on opportunities to build wealth through home equity. Denial of those opportunities for many decades is largely responsible for today’s large wealth gap between Whites and African Americans in the United States.

The Fair Housing Act of 1968 made it illegal to discriminate in renting and selling homes but that would not be the end of racist policies. Passed nearly two decades earlier, the Federal Housing Act of 1949 allowed the federal government to aid cities in clearing what was termed as blighted conditions to allow for newer development. Ironically, the substandard conditions were usually a result of decades of municipal neglect.

Disguised as a way to help low-income blighted communities, the Federal Housing Act of 1949 paved the way for the removal of low-income minority communities for development projects that benefited other communities. The government paid residents an average of $3,000 for their homes with a promise that new, affordable, and better houses would be built in the neighborhood for the displaced residents to purchase. However, in most cities including Roanoke, that promise was never met.

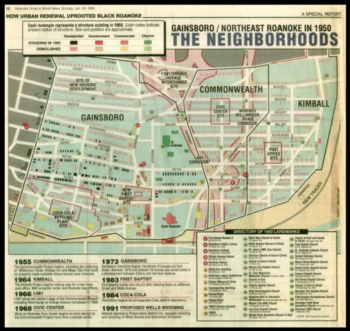

These programs often resulted in the destruction of African-American neighborhoods, perceived as blighted through biased eyes. Residents of these neighborhoods viewed these neighborhoods differently than those looking in from the outside. What may have seemed to be run down areas were actually vibrant, complete neighborhoods where residents had access to stores, pharmacies, schools — everything needed for day-to-day life. Residents knew their neighbors and there was a strong sense of community.

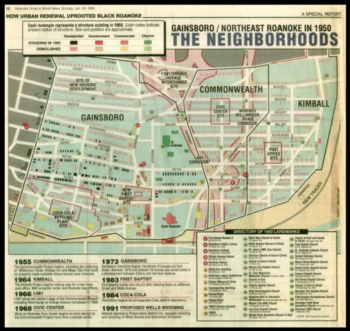

Bishop, Mary. “Street by street, block by block: How urban renewal uprooted black Roanoke.” The Roanoke Times (1995).

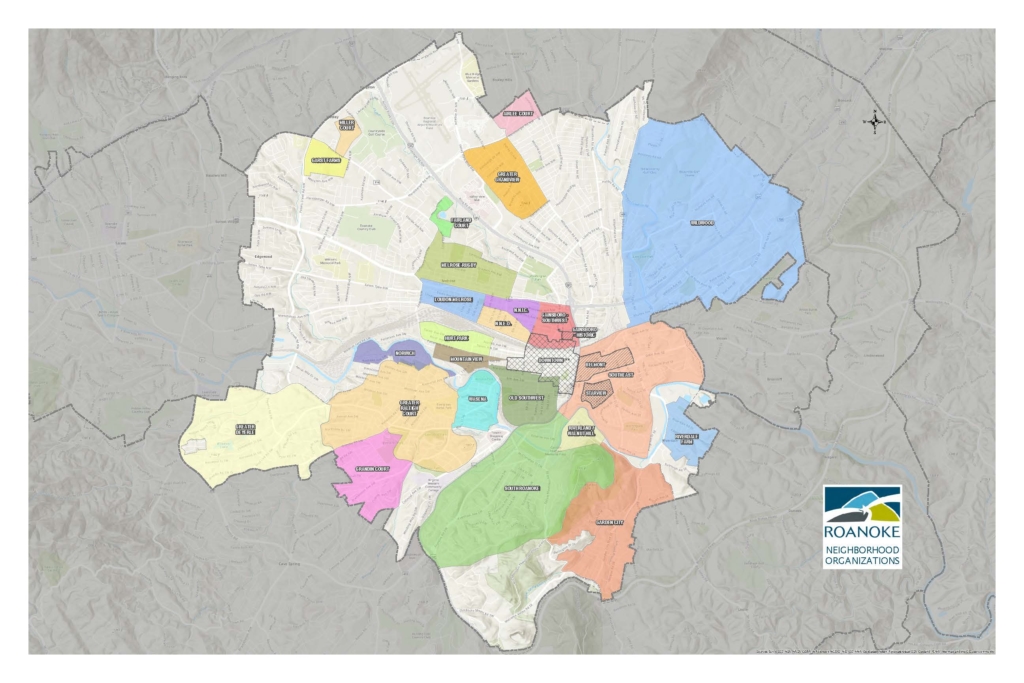

In Roanoke, neighborhood urban renewal projects were focused on the African-American neighborhoods in northeast and northwest Roanoke adjacent to downtown. All told, 83 acres were cleared for Interstate 581, the Civic Center, Post Office, Coca-Cola plant, and other commercial and industrial uses. No houses were built back in the area forcing residents to relocate to other parts of the City, primarily in the northwest sector. Residents lost wealth in the form of home equity, as homes were purchased at low dollar amounts and displaced residents were resettled, often in rental units or public housing.

Urban renewal wasn’t just a housing issue, but the displacement shattered an intangible sense of community . In Roanoke, this effect was discussed in Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America and What We Can Do About It by Mindy Fullilove and documented in Mary Bishop’s special report to the Roanoke Times: How Urban Renewal Uprooted Black Roanoke.

Moving Forward as an Equitable City

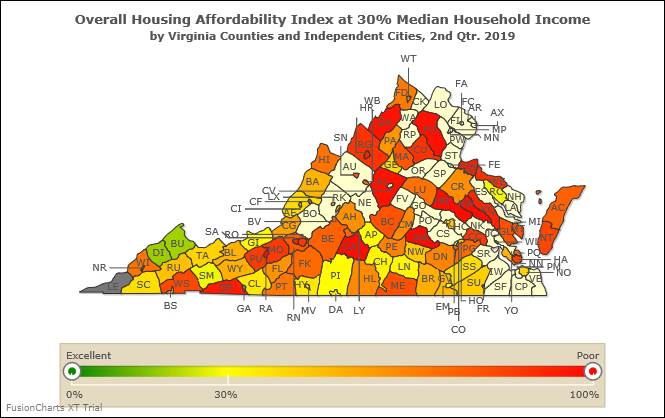

The consequences of segregation laws, real estate practices, and urban renewal are evident today, not just in the City’s development patterns physically, but also socially, economically, and psychologically. Today, consequences are manifested in identifiable neighborhood patterns that show worse health outcomes, less economic mobility, poorer education levels, and lower employment.

Those disparate outcomes are pronounced in the African American communities located in the northwest quadrant of the City. However, these disparate patterns of health outcomes, economic mobility, educational attainment and employment are not isolated to those neighborhoods.

As a community, we must understand how intentional practices created barriers to the success of African Americans and other residents of Roanoke. As we learn and reconcile these inequities, we must also look forward to how we can apply these lessons to all individuals regardless of race, ethnicity, age, gender, gender identity, disability, sexual orientation, and any other characteristic upon which people are discriminated against, oppressed, or disadvantaged.

As the City continues to grow and becomes increasingly more diverse, we must understand the needs and concerns of all residents and strive to build trust, support upward mobility, remove barriers affecting neighborhood choice, champion an inclusive community, and provide services equitably.

Interwoven Equity is the idea that decision making and policy making are based on principles of equity and are examined for bias and potential unintended consequences for any specific group of people. To that end, five priorities emerged:

- Trust

- Break the Cycle of Poverty

- Neighborhood choice

- Inclusion Culture

- Service Delivery

Welcoming Roanoke

As the city moves forward, it is vital that we project an atmosphere of inclusiveness to lifelong residents and newcomers. The Welcoming Roanoke Plan addresses how we can better serve new residents in our city and gives the city a roadmap to creating a welcoming city for all including immigrants and refugees. While the Welcoming Roanoke Plan is a separate document, the spirit of being a welcoming city is present throughout this plan.

Urban Sustainability Directors Network’s Video on Driving Toward Equity

This video outlines the many ways racism is reflected in today’s society and ways municipal leaders can work to stop it. This video has the following goals:

- Gain an increased understanding of a racial equity framework, including definitions of key terms such as racial equity, implicit and explicit bias, and individual, institutional, and structural racism.

- Learn about examples of structural racism and the relationship between structural racism and sustainability.

- Consider opportunities to use your work on sustainability to move a racial equity agenda in your own city

Priority One: Trust

While overtly discriminatory policies of the past have largely been removed, there is still a responsibility for City government and its current leadership to regain trust following the trauma experienced by African American communities. For the community to thrive as a whole, the City government must work to build trust through its actions.

Priority Two: Break the Cycle of Poverty

A variety of factors affect people in poverty in ways that make it difficult to break the cycle of poverty. This priority focuses on policies that provide pathways to upward mobility and remove the obstacles that get in the way of success.

Priority Three: Neighborhood Choice

Priority Four: Inclusive Culture

Priority Five: Service Delivery

This priority focuses on services provided by the City of Roanoke. It is crucial that services are provided equitably and in ways that are accessible to all residents.

Defining Equity

Roanoke will not reach its full potential as a community unless each citizen has the opportunity to reach their full potential. Equity involves the fair distribution of investments and services and the removal of institutional or structural policies that can be barriers to success. Equity is the idea that different groups have different needs and should be provided services determined by their needs. If the City gives everyone equal treatment regardless of their individual needs, then it may be unintentionally creating disparate outcomes.

Visualizing Health Equity: One Size Does Not Fit All Infographic by RWJF on RWJF.org

In this plan, the term interwoven equity means that ideas about equity are woven into or embedded within each theme of the plan.

The intent of this plan is to ensure equity in our policies as they relate to race, ethnicity, age, gender, gender identity, disability, sexual orientation, and any other characteristics upon which people are discriminated against, oppressed, or disadvantaged. This plan dedicates most discussion to racial equity because of its profound impact on the physical development of the City.

A History of Inequity

Any conversation on equity must acknowledge racist policies that existed throughout the country and were present here in Roanoke. While openly racist laws may have come and gone, implicit or proxy policies took their place and some have yet to be completely left behind. The consequences of these policies are still felt today, manifested in de facto housing segregation along with persistent disparities in income, education, employment, incarceration rates, community health, and a pronounced wealth gap.

Throughout much of the 20th century, African Americans were subjected to a coordinated effort of government and real estate interests that limited where they could live. Jim Crow laws started spreading through the south just as Roanoke was incorporated in 1882. In 1911, Roanoke adopted residential segregation ordinances that remained in place for years until a 1917 Supreme Court decision declared such laws unconstitutional. Roanoke eventually repealed these ordinances, but private interests continued to enforce segregation effectively through private restrictive covenants in deeds and through redlining. Redlining was the practice of mortgage and mortgage insurance companies that rated neighborhoods based on perceived risk of default. “Hazardous” or “Fourth grade” classifications were given to low income neighborhoods disproportionately occupied by African American families.

These practices, individually and cumulatively, had insidious results. Limiting African American families to a relatively small area of the City and limiting the number of housing units available to them. Segregation induced scarcity which drove up rents for Black residents. For those who could get a mortgage within the redlined areas, the interest rates were much higher. Barriers to home purchase put constraints on opportunities to build wealth through home equity. Denial of those opportunities for many decades is largely responsible for today’s large wealth gap between Whites and African Americans in the United States.

The Fair Housing Act of 1968 made it illegal to discriminate in renting and selling homes but that would not be the end of racist policies. Passed nearly two decades earlier, the Federal Housing Act of 1949 allowed the federal government to aid cities in clearing what was termed as blighted conditions to allow for newer development. Ironically, the substandard conditions were usually a result of decades of municipal neglect.

Disguised as a way to help low-income blighted communities, the Federal Housing Act of 1949 paved the way for the removal of low-income minority communities for development projects that benefited other communities. The government paid residents an average of $3,000 for their homes with a promise that new, affordable, and better houses would be built in the neighborhood for the displaced residents to purchase. However, in most cities including Roanoke, that promise was never met.

These programs often resulted in the destruction of African-American neighborhoods, perceived as blighted through biased eyes. Residents of these neighborhoods viewed these neighborhoods differently than those looking in from the outside. What may have seemed to be run down areas were actually vibrant, complete neighborhoods where residents had access to stores, pharmacies, schools — everything needed for day-to-day life. Residents knew their neighbors and there was a strong sense of community.

Bishop, Mary. “Street by street, block by block: How urban renewal uprooted black Roanoke.” The Roanoke Times (1995).

In Roanoke, neighborhood urban renewal projects were focused on the African-American neighborhoods in northeast and northwest Roanoke adjacent to downtown. All told, 83 acres were cleared for Interstate 581, the Civic Center, Post Office, Coca-Cola plant, and other commercial and industrial uses. No houses were built back in the area forcing residents to relocate to other parts of the City, primarily in the northwest sector. Residents lost wealth in the form of home equity, as homes were purchased at low dollar amounts and displaced residents were resettled, often in rental units or public housing.

Urban renewal wasn’t just a housing issue, but the displacement shattered an intangible sense of community . In Roanoke, this effect was discussed in Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America and What We Can Do About It by Mindy Fullilove and documented in Mary Bishop’s special report to the Roanoke Times: How Urban Renewal Uprooted Black Roanoke.

The consequences of segregation laws, real estate practices, and urban renewal are evident today, not just in the City’s development patterns physically, but also socially, economically, and psychologically. Today, consequences are manifested in identifiable neighborhood patterns that show worse health outcomes, less economic mobility, poorer education levels, and lower employment.

Those disparate outcomes are pronounced in the African American communities located in the northwest quadrant of the City. However, these disparate patterns of health outcomes, economic mobility, educational attainment and employment are not isolated to those neighborhoods.

As a community, we must understand how intentional practices created barriers to the success of African Americans and other residents of Roanoke. As we learn and reconcile these inequities, we must also look forward to how we can apply these lessons to all individuals regardless of race, ethnicity, age, gender, gender identity, disability, sexual orientation, and any other characteristic upon which people are discriminated against, oppressed, or disadvantaged.

As the City continues to grow and becomes increasingly more diverse, we must understand the needs and concerns of all residents and strive to build trust, support upward mobility, remove barriers affecting neighborhood choice, champion an inclusive community, and provide services equitably.

Interwoven Equity is the idea that decision making and policy making are based on principles of equity and are examined for bias and potential unintended consequences for any specific group of people. To that end, five priorities emerged:

- Trust

- Break the Cycle of Poverty

- Neighborhood choice

- Inclusion Culture

- Service Delivery

Welcoming Roanoke

As the city moves forward, it is vital that we project an atmosphere of inclusiveness to lifelong residents and newcomers. The Welcoming Roanoke Plan addresses how we can better serve new residents in our city and gives the city a roadmap to creating a welcoming city for all including immigrants and refugees. While the Welcoming Roanoke Plan is a separate document, the spirit of being a welcoming city is present throughout this plan.

Urban Sustainability Directors Network’s Video on Driving Toward Equity

This video outlines the many ways racism is reflected in today’s society and ways municipal leaders can work to stop it. This video has the following goals:

- Gain an increased understanding of a racial equity framework, including definitions of key terms such as racial equity, implicit and explicit bias, and individual, institutional, and structural racism.

- Learn about examples of structural racism and the relationship between structural racism and sustainability.

- Consider opportunities to use your work on sustainability to move a racial equity agenda in your own city

Priority One: Trust

While overtly discriminatory policies of the past have largely been removed, there is still a responsibility for City government and its current leadership to regain trust following the trauma experienced by African American communities. For the community to thrive as a whole, the City government must work to build trust through its actions.

Priority Two: Break the Cycle of Poverty

A variety of factors affect people in poverty in ways that make it difficult to break the cycle of poverty. This priority focuses on policies that provide pathways to upward mobility and remove the obstacles that get in the way of success.

Priority Three: Neighborhood Choice

Priority Four: Inclusive Culture

Priority Five: Service Delivery

This priority focuses on services provided by the City of Roanoke. It is crucial that services are provided equitably and in ways that are accessible to all residents.