Land Use

Background

The idea of regulating and arranging uses of land began almost as soon as human settlement began and remains the very essence of city planning. Early planning prescribed how various essential uses—the public square, sites for civic buildings, and the streets—are organized on the landscape.

During the 20th century, rapid urbanization led to land use regulation becoming a core activity of local governments. Rather than organizing important activities, however, land use regulation evolved into a practice of excluding urban activities from one another. City planning during the second half of the 20th century had a heavy focus on separating land uses. Zoning emerged as a tool to exclude noxious industrial uses from residential areas, but then cities started using it to exclude commercial uses from residential areas. Eventually, it became common to designate vast areas of the city exclusively for single-family dwellings, prohibiting all other uses including other types of residential buildings.

Automobiles facilitated this separation, making it relatively easy to travel among distant places for everyday activities. Cars became necessities for living, working, learning, recreating, and shopping. City planning then became centered on accommodating vehicles. Unique downtowns and neighborhood centers gave way to commercial strips and malls. Subdivisions replaced neighborhoods. Industries located in suburban industrial parks, far away from where the workers lived. The result was a patchwork of isolated activities with little relation to the larger community; these replaced the complete neighborhood patterns that existed prior to the 1950s.

Cars changed where commercial areas developed and they fundamentally changed how they developed. Buildings, once located with their fronts placed along the sidewalk, were pushed back behind fields of parking. Parking lots got bigger and bigger, in part due to minimum parking requirements imposed by zoning. In just a few decades, there was a major shift in how we used land. Prior to WWII, buildings typically occupied all or nearly all of their sites. Now, most land on a site is dedicated to parking and the building rarely occupies even half of the lot. These parking lots, which sit mostly empty, are major contributors to higher local temperatures in summer, water pollution, flash flooding, and destruction of the natural environment. What’s more, they contribute little to municipal revenues.

Meanwhile, a profoundly harmful cycle of commercial expansion and abandonment began in the early 1960s. As suburbanization ramped up, the first generation of malls and strip development began to lure shopping and services away from downtown and neighborhood centers.

Locally, Crossroads Mall, Roanoke-Salem Plaza, and Towers Mall popped up in 1961 and 1962. Tanglewood, the Valley’s first regional mall, opened in 1973. It captured much of the retail activity of those first shopping centers. And so the gleaming centers of modernity of the 1960s started to become urban liabilities in the 70s and 80s. As anchor stores departed from Crossroads and Roanoke-Salem Plaza, these complexes devolved into centers for less intensive activity like office and warehouse retail, with unused parking areas being sold off as outparcels (only Towers would endure as a viable center). Once-vibrant commercial strips like Williamson Road and Melrose Avenue began to struggle with chronic vacancies, blight, and marginal businesses. They have not improved significantly since the 70s. After decades of hoping the market would intervene, there are no signs that these places will see a revival without considerable intervention.

Tanglewood’s dominance would not last for long. Valley View Mall opened in 1985. An even larger regional mall along with the nearby power centers like Towne Square and Valley View Crossing would trigger Tanglewood’s decline in the ensuing decades.

As the malls and strips battled for retail dominance, downtown and neighborhood centers were on life support as economic activity was siphoned off to the suburbs. To keep Roanoke’s beloved downtown relevant, civic leaders scrambled to invest millions into signature projects like Center in the Square and the Market Building. Public funds went to parking structures and infrastructure upgrades.

Among planners and civic leaders, there was universal agreement about the importance of saving downtown. People develop emotional attachments to places like downtown and neighborhood centers and they will put a lot of effort into saving them. In contrast, there is no attachment to places with generic, windowless buildings located behind parking lots, distinguished from one another only by their signs next to the road. Few care when an old strip mall building gets torn down.

The last half of the 20th century saw the invention of a lot of disposable products like lighters, pens, and diapers, to name a few. Likewise, most commercial buildings became, in effect, disposable. Constructed with cheap materials, with no architectural features, few windows, and only to the very minimum safety codes, they were designed for a life span of only a few decades. While most disposable consumer products made their way into landfills eventually, a landscape of disposable buildings remains. In a practice that persists today, commercial buildings were designed for a specific tenant with no thought of the next occupant. Once the original user moves on, they can be difficult to adapt to a new business, so they may sit vacant for years.

These wasteful, indulgent cycles leave us with acres of places that are unlovable—places that few would deem worth preserving. The places they create leave us with an urgency to develop the next thing in the name of progress and growth. Of course, when we move on, the places left behind don’t disappear. They persist as they are exploited for whatever economic value they have left. Unfortunately, decaying strips and centers seem normal to us because they are ubiquitous in every American city. The situation is not expected to improve as retail experts consistently point to a current oversupply of retail space in the US. The amount, 23 square feet per person, is by far the highest in the world and is considered too much, even if shifts to online retail were not occurring.

Past planning approaches employed a strategy of containment and hope that revitalization or redevelopment would come along some day through creative zoning and incentives. In the past two decades, however, positive results have been limited to fairly small areas, with the South Jefferson Redevelopment Area representing the only successful conversion of a significant amount of land to improved uses. It involved bold action in the form of acquisition, clearing, and cleanup to make way for new development according to a plan.

The practice of city planning involves recognizing problems that exist now or will likely exist in the future, and recommending interventions that promise to improve the future condition. The cycles of abandonment described above show no signs of ending and are harmful to the City, with effects that extend into every theme discussed by this plan – equity, community health, our economy, and our environment. We have a responsibility to acknowledge that we need to a new vision for commercial development in order to have a resilient economy and a clean, healthy environment. City planners have a responsibility to recommend policies that will begin the process of repairing our underperforming places and stop the cycle of commercial obsolescence and abandonment. Fixes will not be easy, nor short term, nor painless. Success will depend on our collective resolve to improve the places that have been left behind and not create any more places that will be the castoffs of the future.

Interventions

In the 1980s and 1990s, planners started to realize the profound negative economic, environmental, and social impacts of such patterns. The New Urbanism movement gained influence as an alternative that simply advocated the natural settlement patterns that would tend to occur in the absence of artificial regulatory interventions. Vision 2001-2020 adopted the urban design ideas of the movement like integrated neighborhoods and walkability. These concepts certainly should be carried forward in this plan.

Simply put, we advocate development policies that create the kind of places that people value and want to preserve. Maintaining historic structures through revitalization and adaptive reuse play a significant role in creating a unique sense of place. From a future economic standpoint, preservation and rehabilitation strategies are much more feasible and far less costly than acquisition and redevelopment. Fortunately, we know what makes good places because we have hundreds of years of patterns to draw from. New Urbanist ideas about retrofitting suburbia and sprawl repair give us a wide range of tactics to employ. Our challenge is to stand firm as a community with the courage, patience, and confidence to insist on good places.

This plan recommends continued long-range movement away from obsolete policies of excluding land uses and continued movement toward policies that promote (or permit) mixing and diversity. Various activities people engage in every day—sleeping, eating, working, socializing, conducting business, recreation—should be accessible within the neighborhood. Each neighborhood should welcome people of varied demographic dimensions such as income, race or ethnicity, life stage, familial status, housing preference, housing type, and mobility. Such diversity tends to occur naturally in the absence of artificial and deliberate actions to prevent it, so local government’s role is to remove or relax barriers (e.g., exclusive zoning practices).

Allowing natural diversity to occur will enhance accessibility, support, information sharing, learning, and resilience in each neighborhood. This direction will also help to reverse some of the negative equity and environmental impacts that come with exclusion of land uses. Creating good places now will mean that minimal government intervention and resources will be needed in the future to keep those places vibrant in the future.

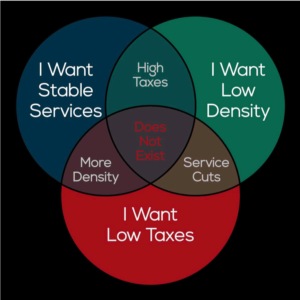

We also need to rethink our assumptions that any new development is beneficial to the city financially. Any developer will state or imply some economic claim in support of a development, and economic value is certainly a valid consideration. Such claims, however, are often made in absolute terms of added real estate value or added sales tax and are not controlled for the development’s consumption of one of the city’s most valuable resources: land. The economic benefit of a development should be considered in light of how much land it occupies. In other words, any benefit should be expressed as benefit per-acre and compared to other development on this basis. That information can help drive rational decision making because we know, in general, that more density and intensity means the development will be a net contribution to the city’s prosperity and can help fund the urban infrastructure that serves it. Likewise we should realize that additional density or intensity might be needed in a development to justify an appropriate package of infrastructure such as sidewalks, street trees, pedestrian scale lighting, and bike lanes.

The priorities for land use are to adopt policies that will support development of complete neighborhoods, design for permanence, and purposeful land use.

Priority: Complete Neighborhoods

The neighborhood has long been recognized as the basic building block of the city. As such, it is vital that we become more inclusive about what constitutes a neighborhood.

A more detailed discussion of the Complete Neighborhoods priority is found within in the Livable Built Environment theme. The discussion here emphasizes the arrangement and interrelationship of dwellings and neighborhood centers.

Priority: Design for permanence

Priority: Purposeful Land Use

Land use is a system where choices should be properly framed and considered by decision-makers. For example, with a relatively slow population growth in the region, adding more commercial land by rezoning for a mall, power center, or strip center means that demand in existing commercial centers, downtown, and neighborhood centers will be impaired to some extent. Preventing development of a wooded parcel in the city with an apartment building may mean that the developer locates it on a wooded parcel in the suburbs. Low-density single-family residential development often happens without objection, but it consumes land while underperforming in terms of municipal revenue vs. service demand.

Land use is a system where choices should be properly framed and considered by decision-makers. For example, with a relatively slow population growth in the region, adding more commercial land by rezoning for a mall, power center, or strip center means that demand in existing commercial centers, downtown, and neighborhood centers will be impaired to some extent. Preventing development of a wooded parcel in the city with an apartment building may mean that the developer locates it on a wooded parcel in the suburbs. Low-density single-family residential development often happens without objection, but it consumes land while underperforming in terms of municipal revenue vs. service demand.