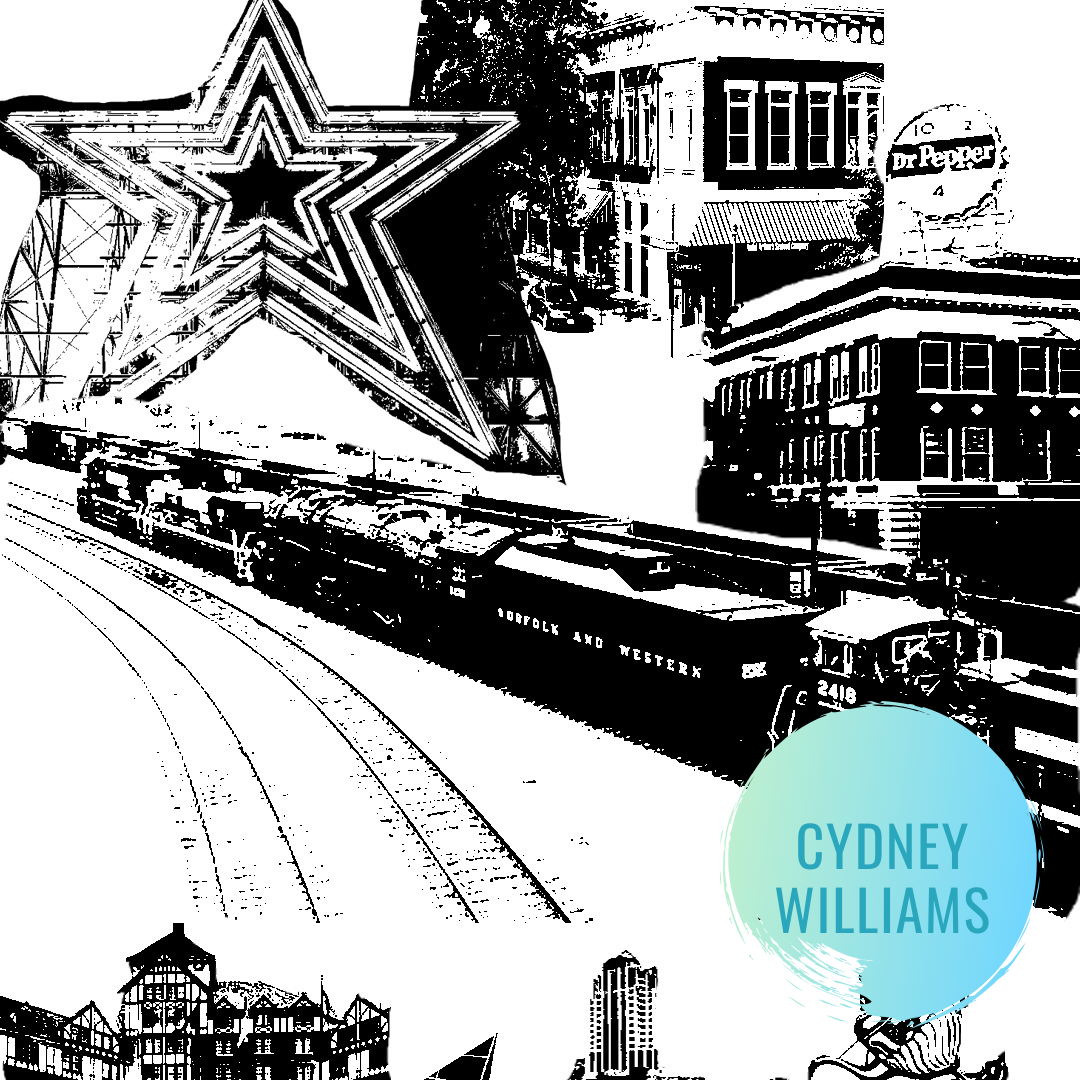

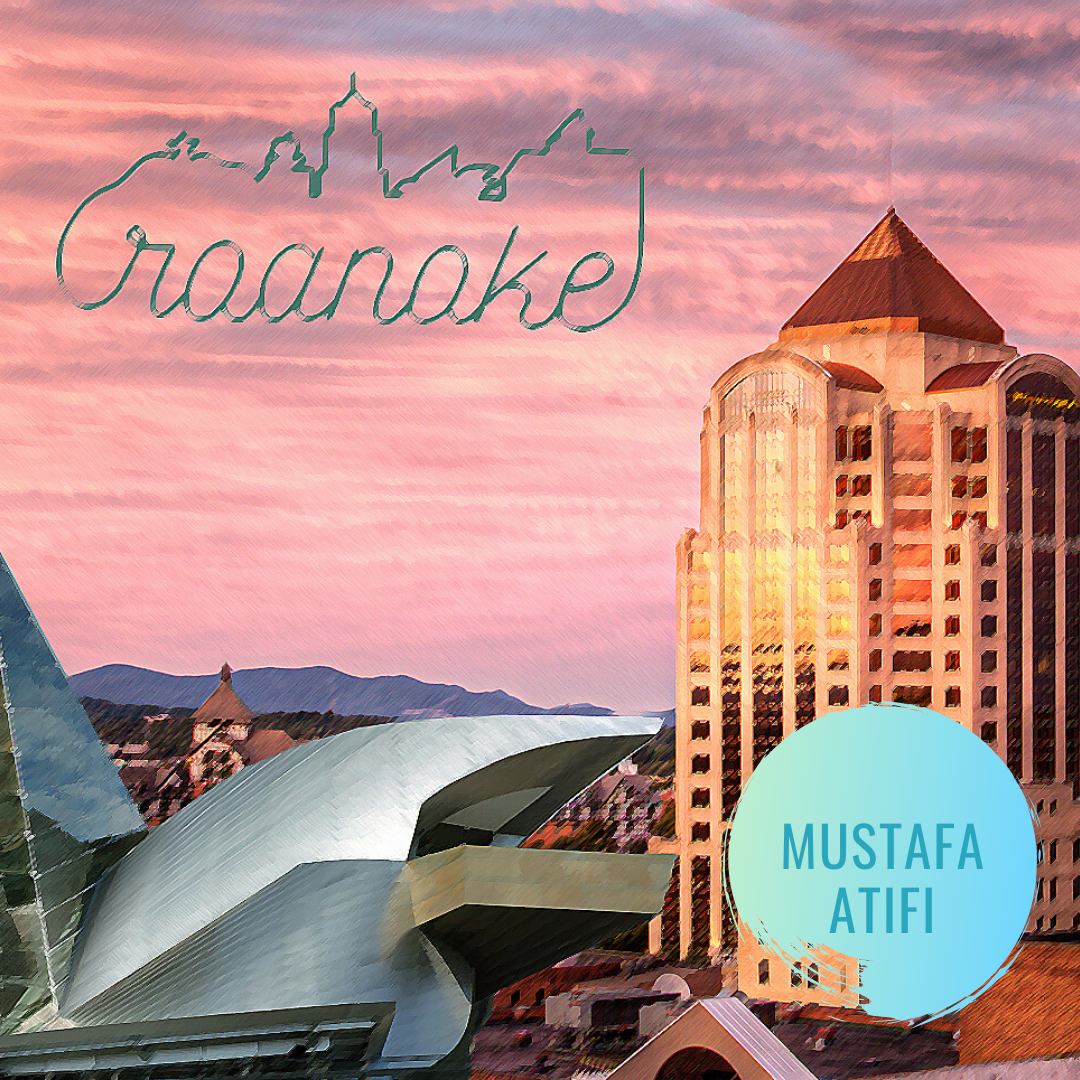

City Plan 2040

City Plan 2040 provides a broad vision for the ideal future for Roanoke with recommendations for implementation over the next 20 years. An extensive public engagement and planning process has culminated in this comprehensive plan.

As you explore the themes of the plan, you’ll discover the most important content: the policies listed under each priority. These policies are intended to guide decision making and future investment in the City over the next 20 years.

Tip: Click highlighted text to reveal definitions or link to source information.

Click here to view a pdf version of the plan.

Vision

City Plan 2040 is a comprehensive plan that will guide investment and decision-making in Roanoke over the next 20 years. The plan recommends policies and actions that work together to achieve the following vision.

In 2040, Roanoke will be:

- A city that considers equity in each of its policies and provides opportunity for all, regardless of background.

- A city that ensures the health and safety of every community member.

- A city that understands its natural assets and prioritizes sustainable innovation.

- A city that interweaves design, services, and amenities to provide high livability.

- A city that collaborates with its neighbors to improve regional quality of life.

- A city that promotes sustainable growth through targeted development of industry, business, and workforce.

Themes

City Plan 2040 is guided by six themes drawn from the American Planning Association’s (APA) Best Practices for Comprehensive Plans.The APA identified six principles necessary to ensure a sustainable community. This plan extends those principles into themes that target pressing community concerns, while anticipating Roanoke’s future needs. These themes will ensure a holistic planning approach that addresses environmental, social, and economic well-being. The following six themes will inform the elements of the plan.

- Interwoven Equity

- Healthy Community

- Harmony with Nature

- Livable Built Environment

- Responsible Regionalism

- Resilient Economy

Elements

The elements of City Plan 2040 consist of priorities, policies, and actions. The plan’s priorities are the most prominent areas of concern identified by the community. The plan’s policies create a decision-making guide to address each priority. The plan’s actions are specific steps needed to implement each policy and achieve the long-term vision of City Plan 2040.

Population

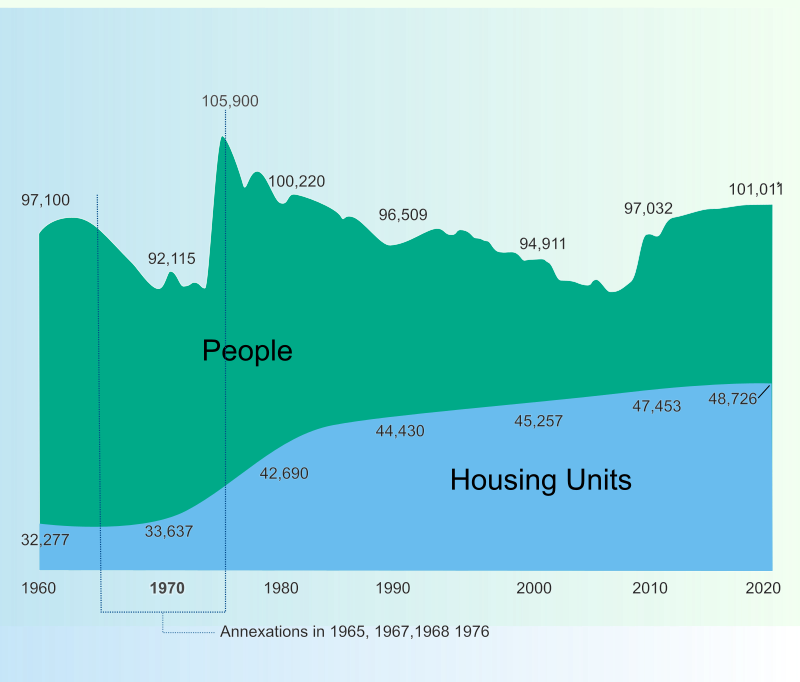

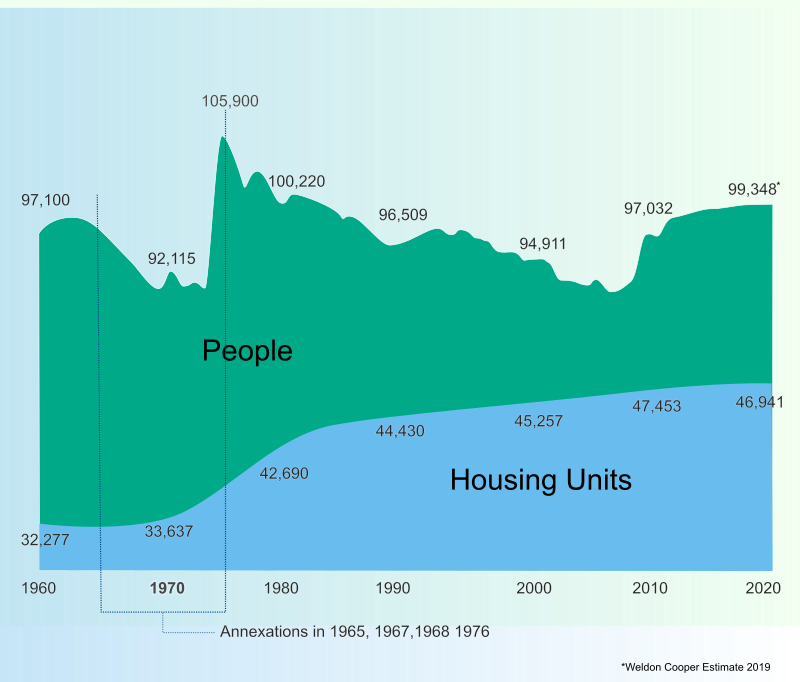

Roanoke’s population has remained relatively stable over the past 60 years. It hasn’t fluctuated more than 10 percent above or below an average of 96,747 during those decades.

Much of Roanoke’s post WWII population gains were the result of annexation of adjacent growth areas. City annexations ended in the mid-1970s when a statewide moratorium was enacted. Roanoke’ population numbers began to decline, falling from a peak just over 105,000 and bottoming out around 92,000. It appeared people might be fleeing the city, but the number of housing units continued to increase; 14,000 net new housing units were created between 1970 and 2010. What was actually happening was that households were getting much smaller. A massive drop in housing density was occurring as the household sizes fell from 2.7 people per household to just 2.0.

Roanoke’s Population and Housing Units

With the increasing attraction of urban living, decades of population decline have ended and Roanoke is seeing modest population increases. According to the University of Virginia’s Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service, Roanoke City’s population is estimated to have just surpassed 100,000 in 2019 and is expected to continue to increase to more than 105,000 in 2040. Roanoke’s population has been growing at a rate of 6.5% since 2009, a rate that is lower than Virginia’s (7.6%) but higher than the national growth rate (5.6%).

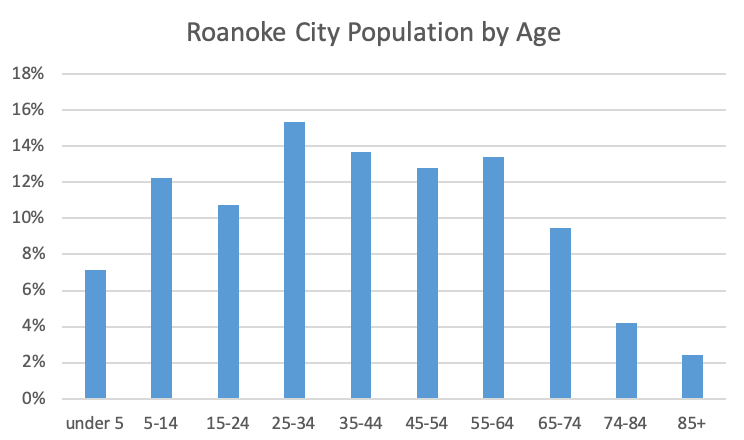

Median age for Roanoke is 38.1 years, slightly higher than that of Virginia and the United States but no so high as to cause concern. A high median age can indicate in-migration of seniors or outmigration of young people. Roanoke’s age distribution creates bell-shaped curve, which indicates a normal age structure.

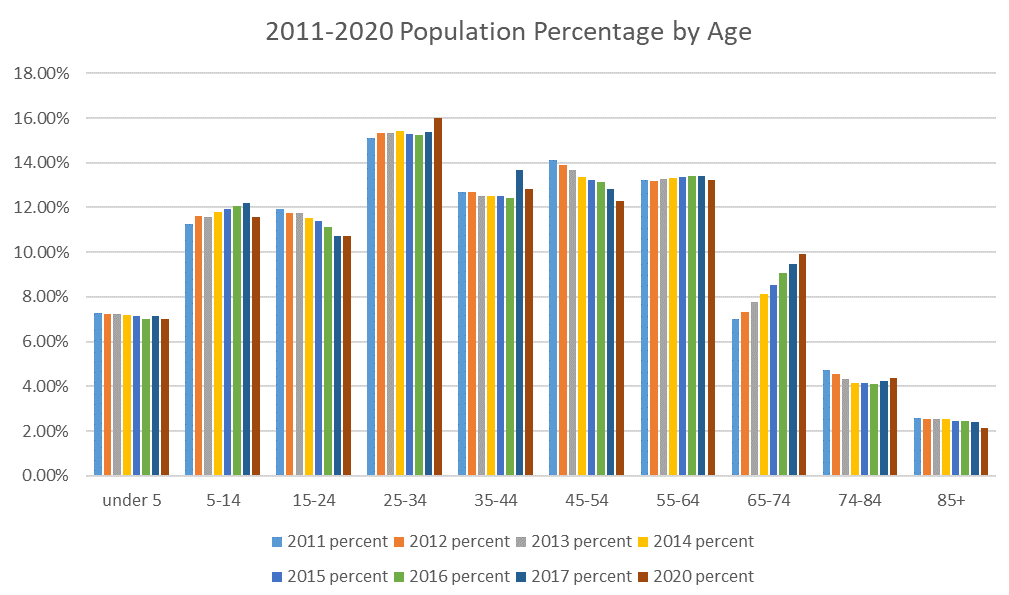

Looking at age brackets over time, one can see changes each year. Again, most of the profile for Roanoke is stable with the exception of the 64-74 bracket which show increases as the Baby Boomers’s cohort moves through. Also notable is the upward trend in the 5-14 age bracket and the downward trend of the 15-24 bracket. However, both changes are relatively slight.

Population by Race

Roanoke’s population is predominantly white (64%) and African American (29%). While still a relatively small population in absolute numbers, the Hispanic population is increasing in terms of growth rates. Considering that People of Color make up over a third of our population, an understanding of our racial and ethnic composition is important to ideas about interwoven equity and inclusion.

Household Size

The average household size for both owner-occupied and renter-occupied Roanoke residents is 2.28 which has increased since 2010. The majority of households have two or fewer people. Single person households account for 37.1% of households and two-person households account for 32.3% of households.

Household Income and Affordability

Roanoke’s median household income of $53,000 is considerably lower than that of Virginia ($90,000) and the United States ($78,000). Housing costs are also considerably lower: the median home value is $133,000 and the median rent is $748 while the median value for Virginia is $248,000 and median rent is $1,135.

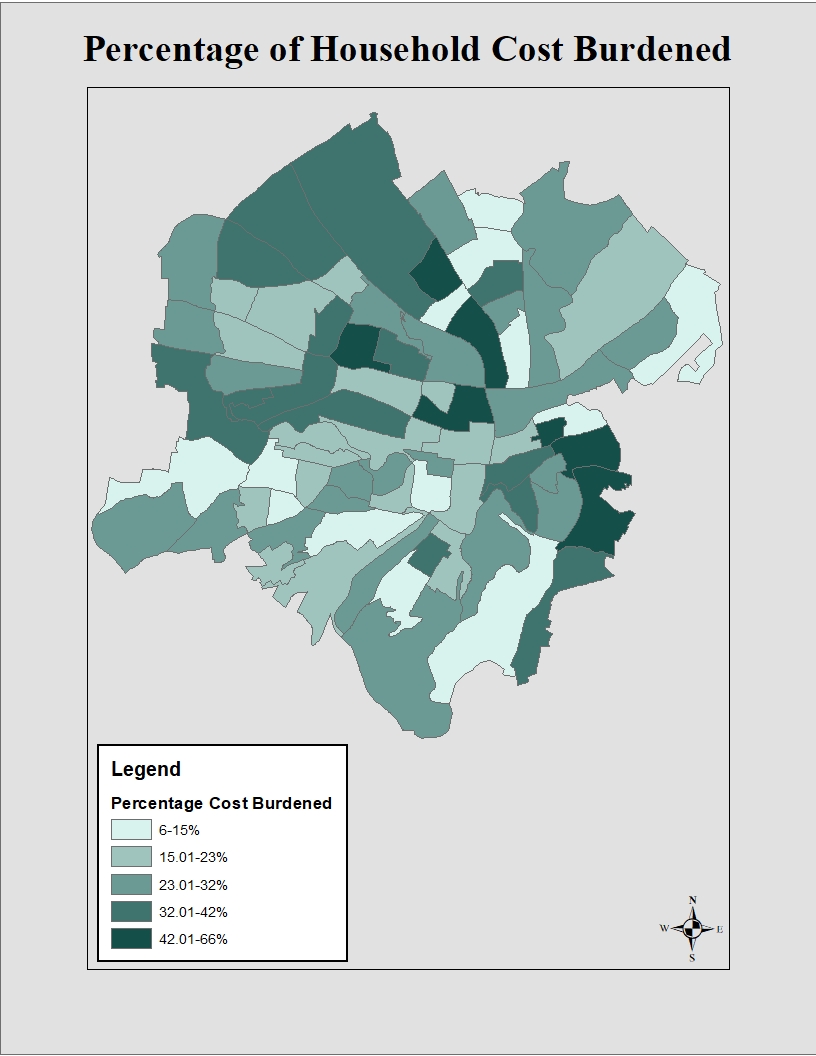

Discussions about affordable housing often lead to the question of ‘Affordable for whom?’ Regional variation in incomes and housing costs can be accounted for when determining affordability by assessing how many and to what extent households are cost burdened by their housing expenses. Cost burdened is defined as spending more than 30% of household income on housing.

Despite Roanoke’s very low housing costs relative to Virginia and the US, we still have a considerable issue with households being cost burdened. The map shows the percentage of households that are cost burdened in each census tract. Darker colors indicate more households are cost burdened. In each year since 2008, more than a third of Roanoke’s households have been cost burdened by monthly mortgage payments or rent. For more details on measuring housing affordability, check out Housing Forward Virginia’s Sourcebook.

Commuting

About 47,000 people commute into Roanoke every day for work and the overwhelming majority use cars as their mode of transportation. Less than ten percent use a different mode of transportation such as biking, walking, or transit. The mean travel time for inbound commuters is 20 minutes, which is lower than that of Virginia at 28 minutes and the United States at 26 minutes.

Upward Mobility

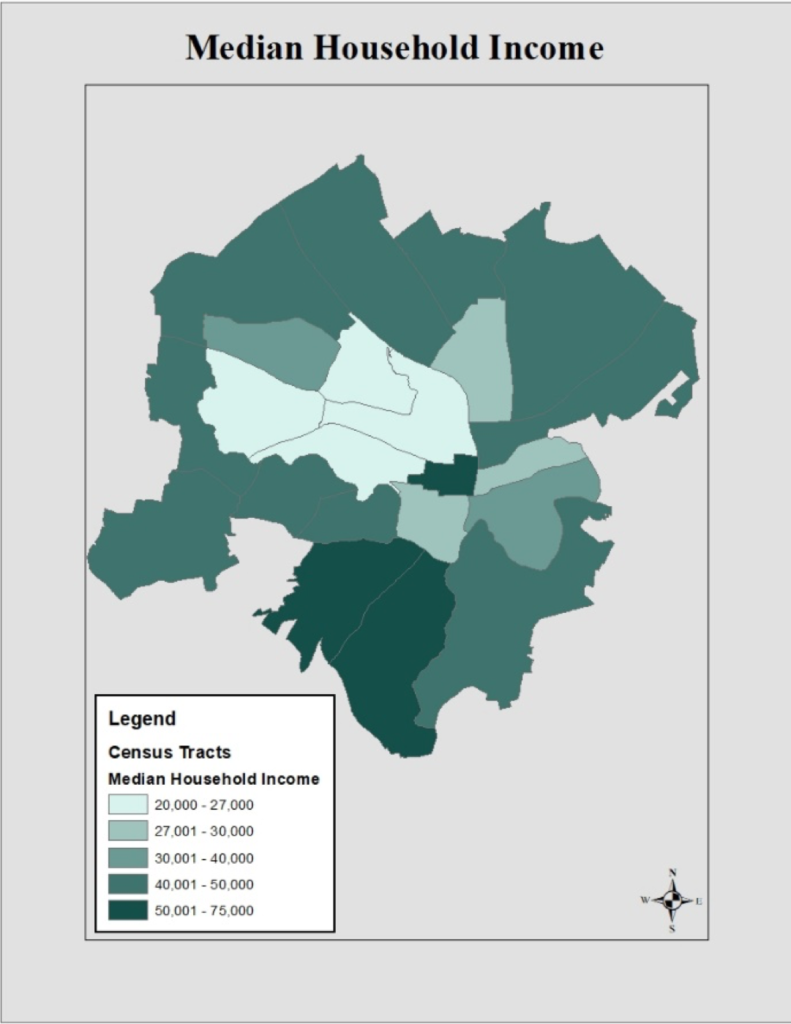

Upward mobility is a persons’ ability to move up in economic status regardless of the economic status they were born into. Cities are beginning to analyze the factors that affect upward mobility as a strategy to address poverty. Segregation by income and race is an important factor in determining a cities degree of upward mobility. The map below shows the median household income in 2016 by census tract. Lower incomes, represented by lighter shades, are concentrated in one area of the city.

The Opportunity Atlas, a collaboration of researchers from the Census Bureau, Harvard, and Brown, enables anyone to explore the details of economic mobility in Roanoke (and beyond).

The map below shows the concentration of white and black populations by census tract. Comparing these maps allows us to see the segregation by income and race for Roanoke.

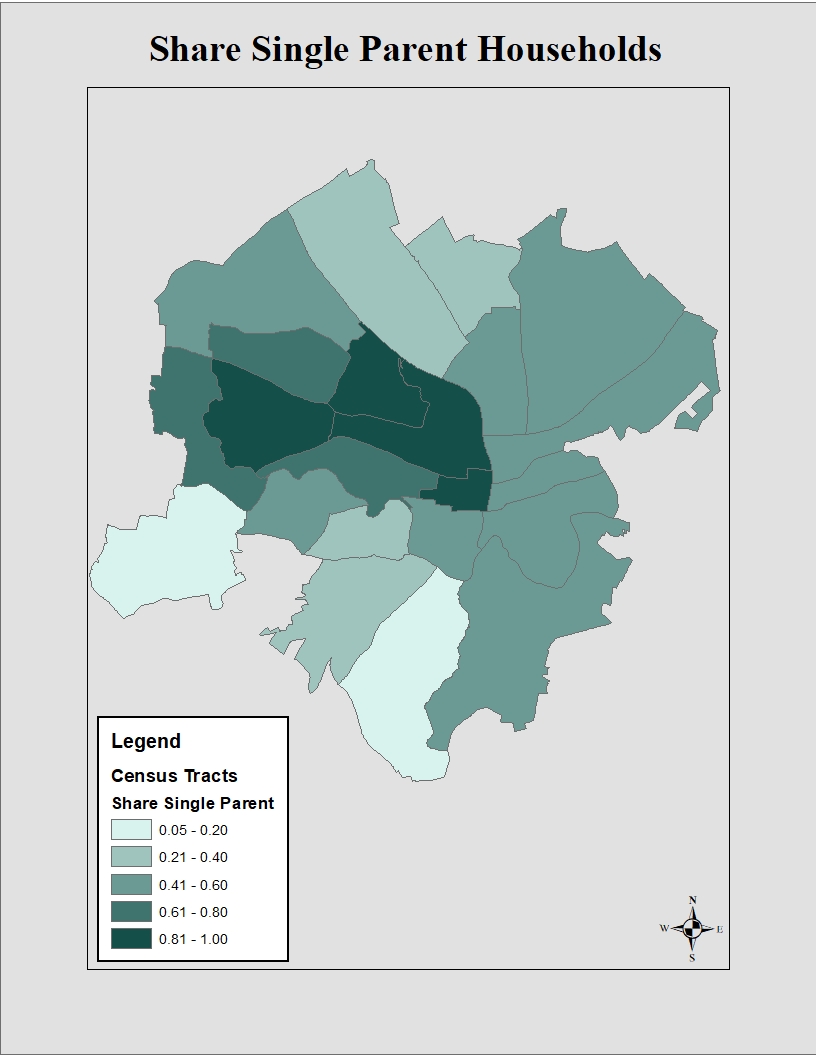

Studies have shown that two parent households are also an important factor when determining upward mobility. The map below shows the share of single parent households by census tract. The same areas that show lower incomes also have the largest share of single parent households. Upward mobility has been an issue that has been identified by various groups in Roanoke. It is important that issues such as upward mobility are recognized and addressed as the city plans for the next twenty years.

All information: U.S. Census Bureau, ACS 5 year estimate, 2016, Factfinder.census.gov

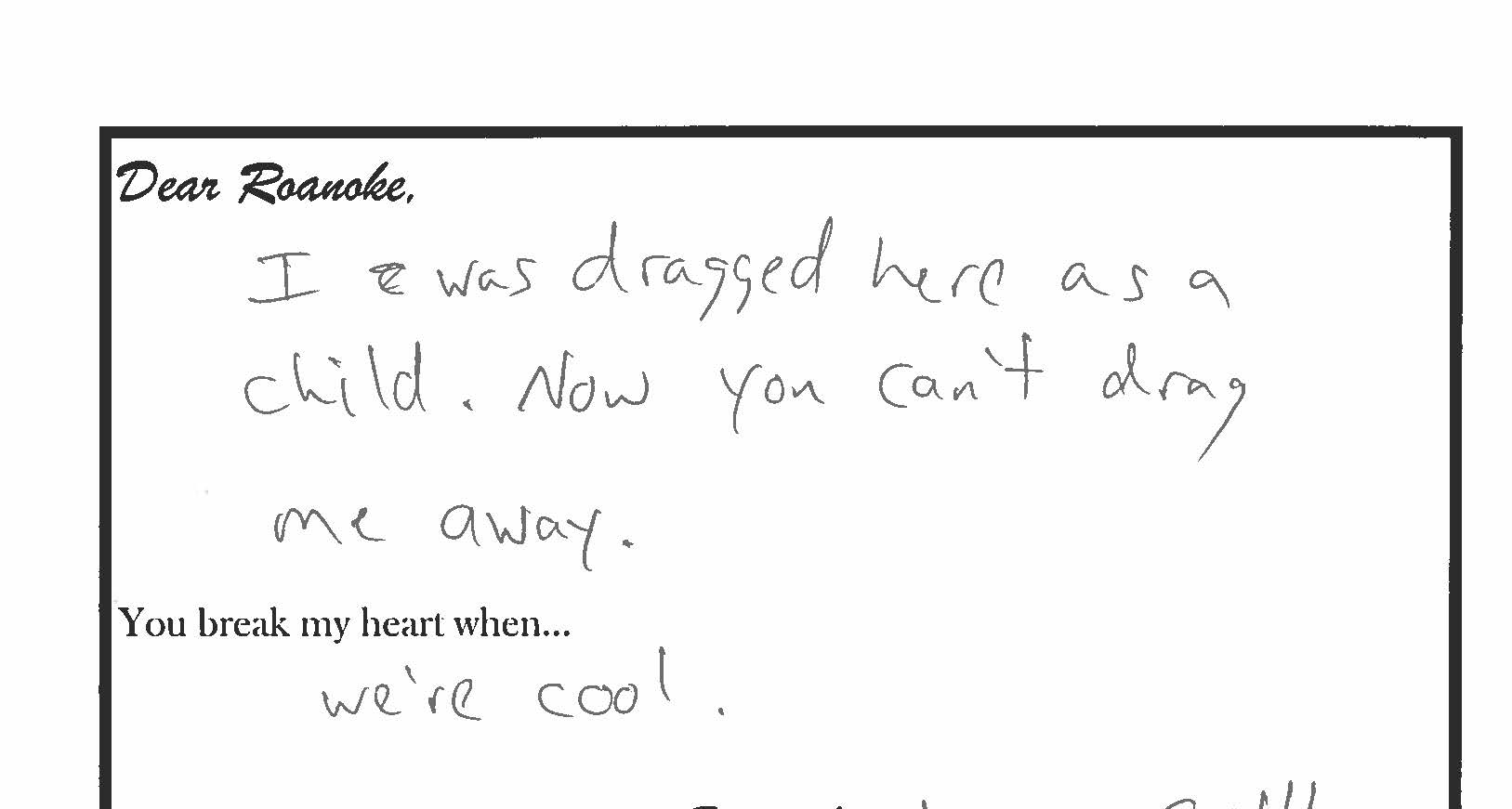

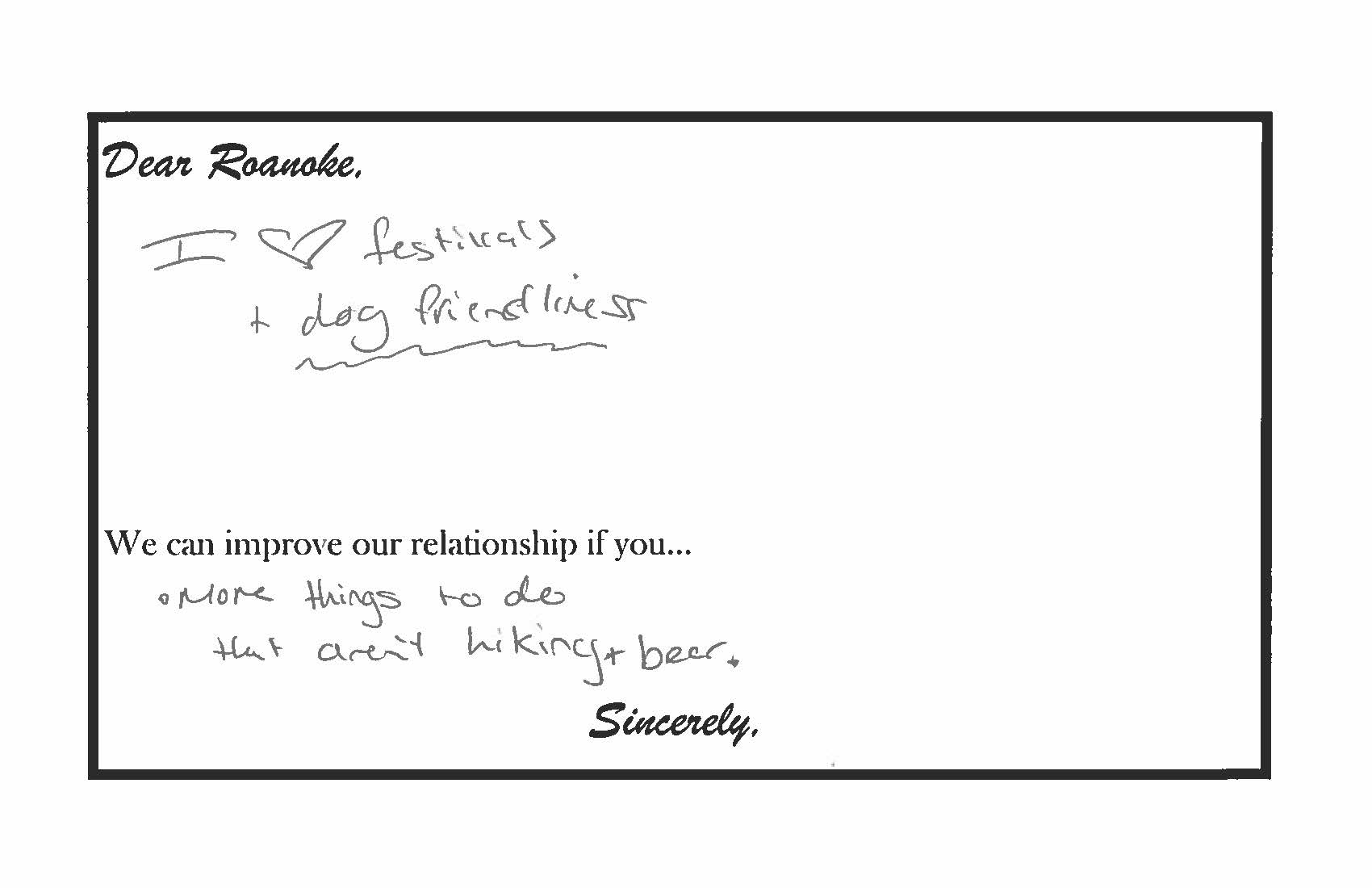

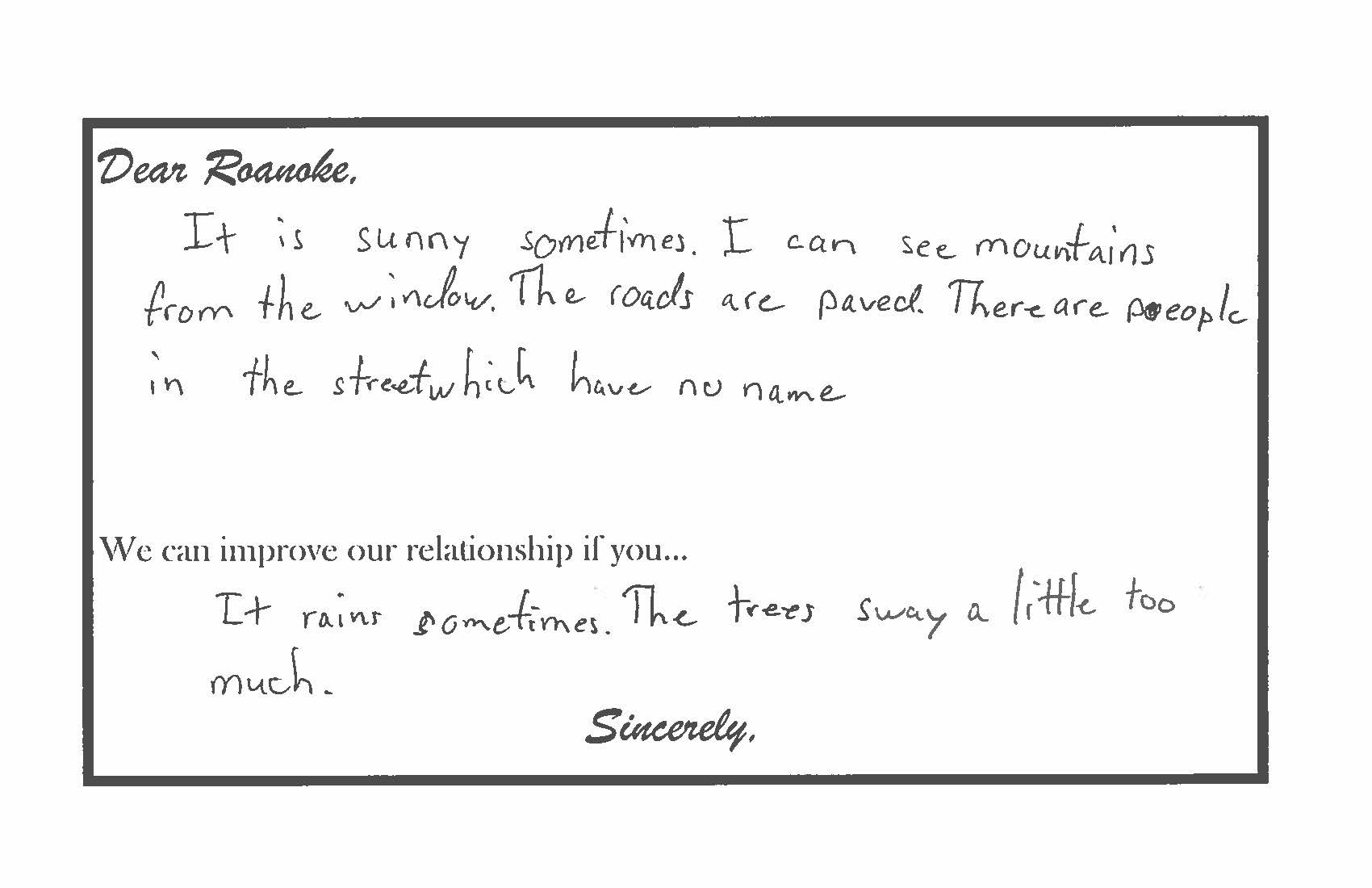

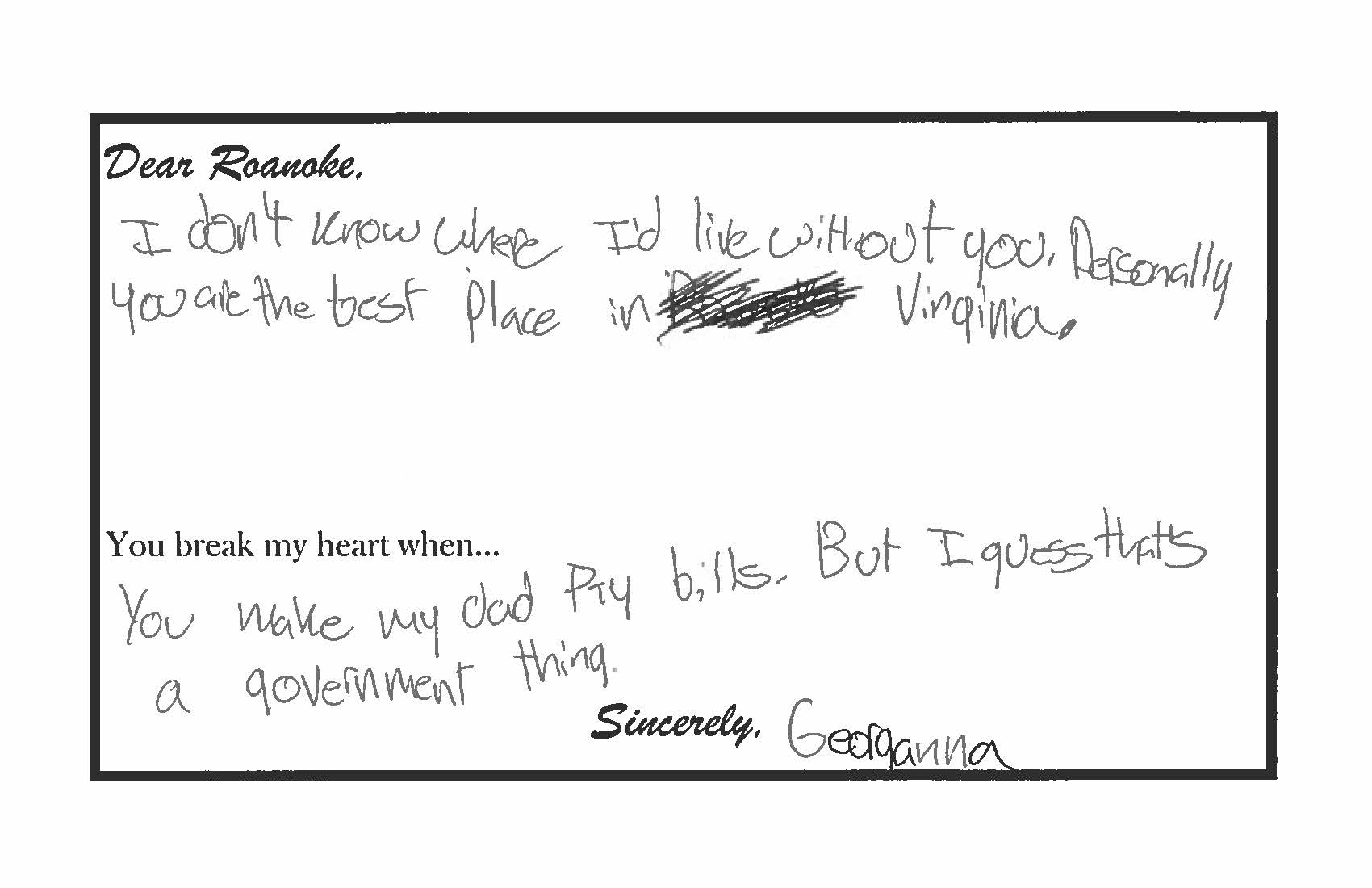

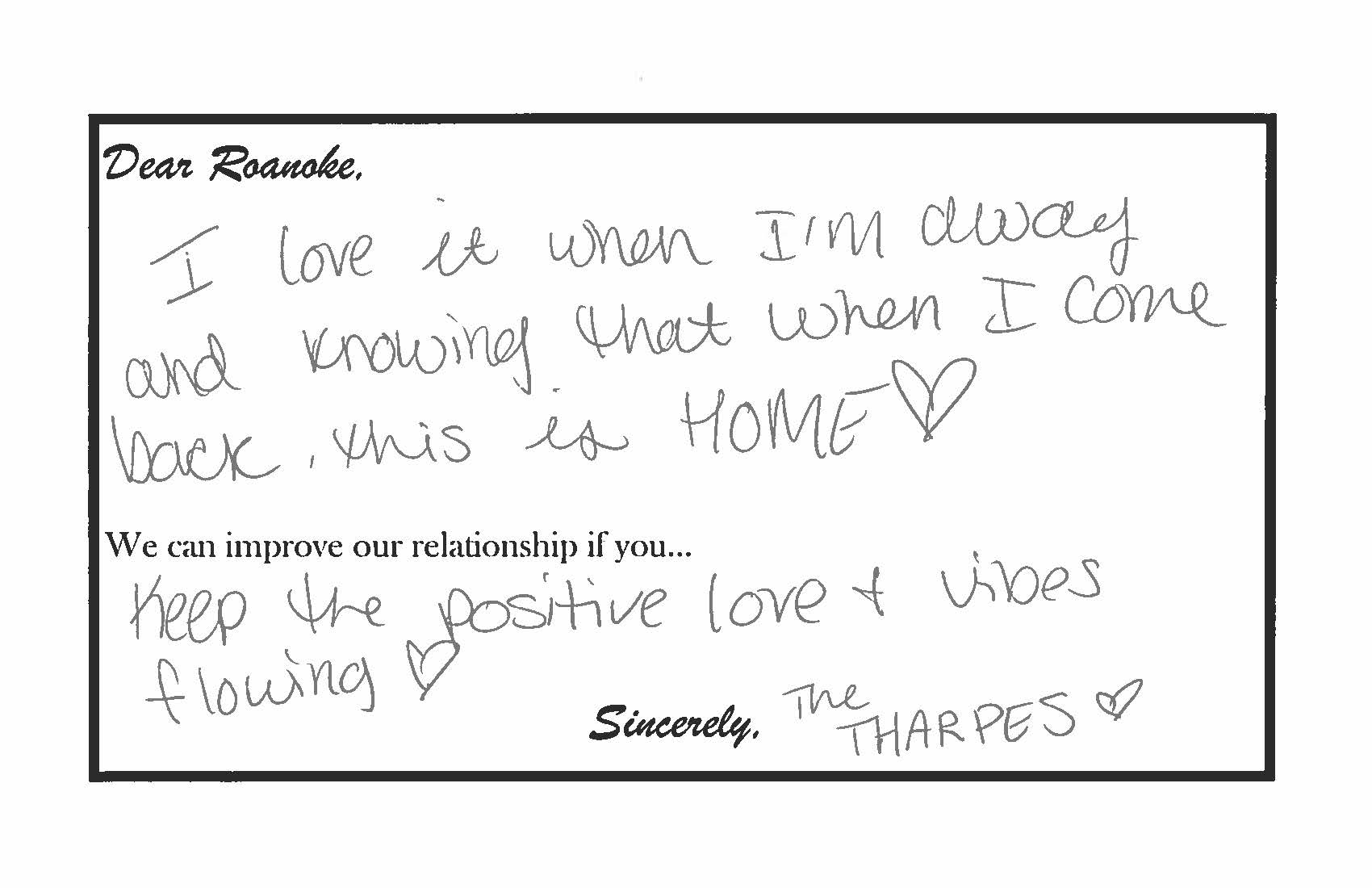

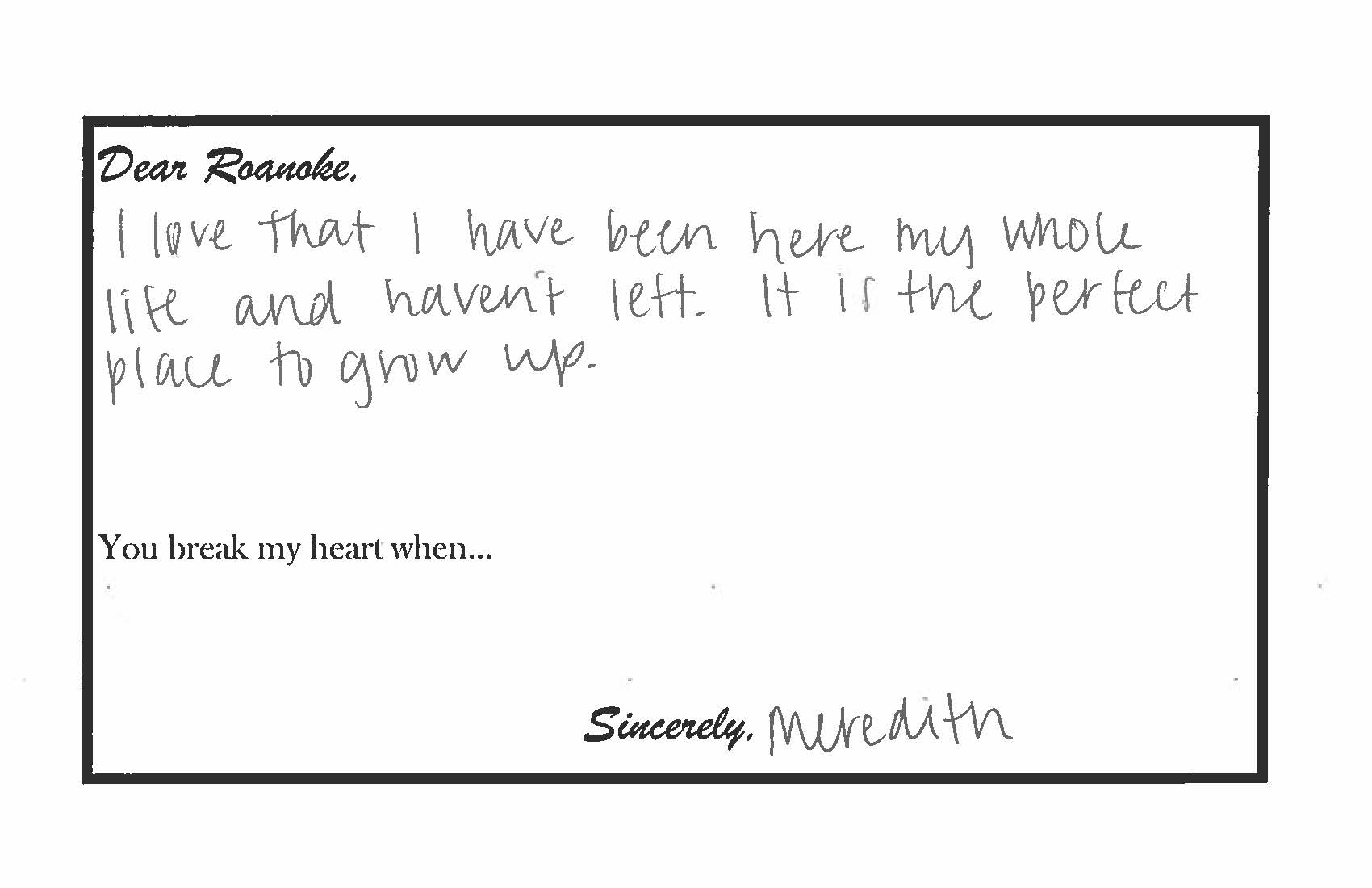

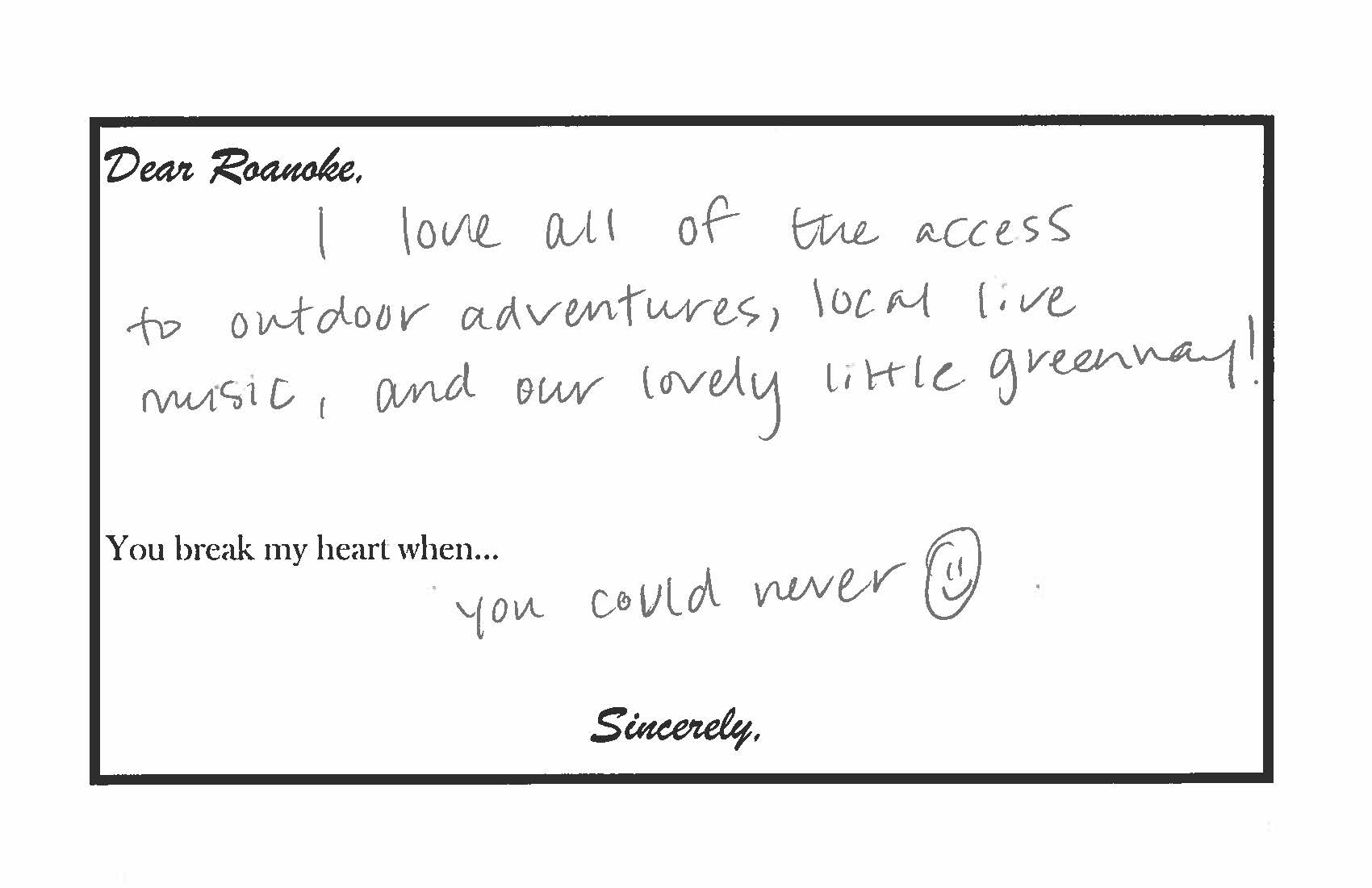

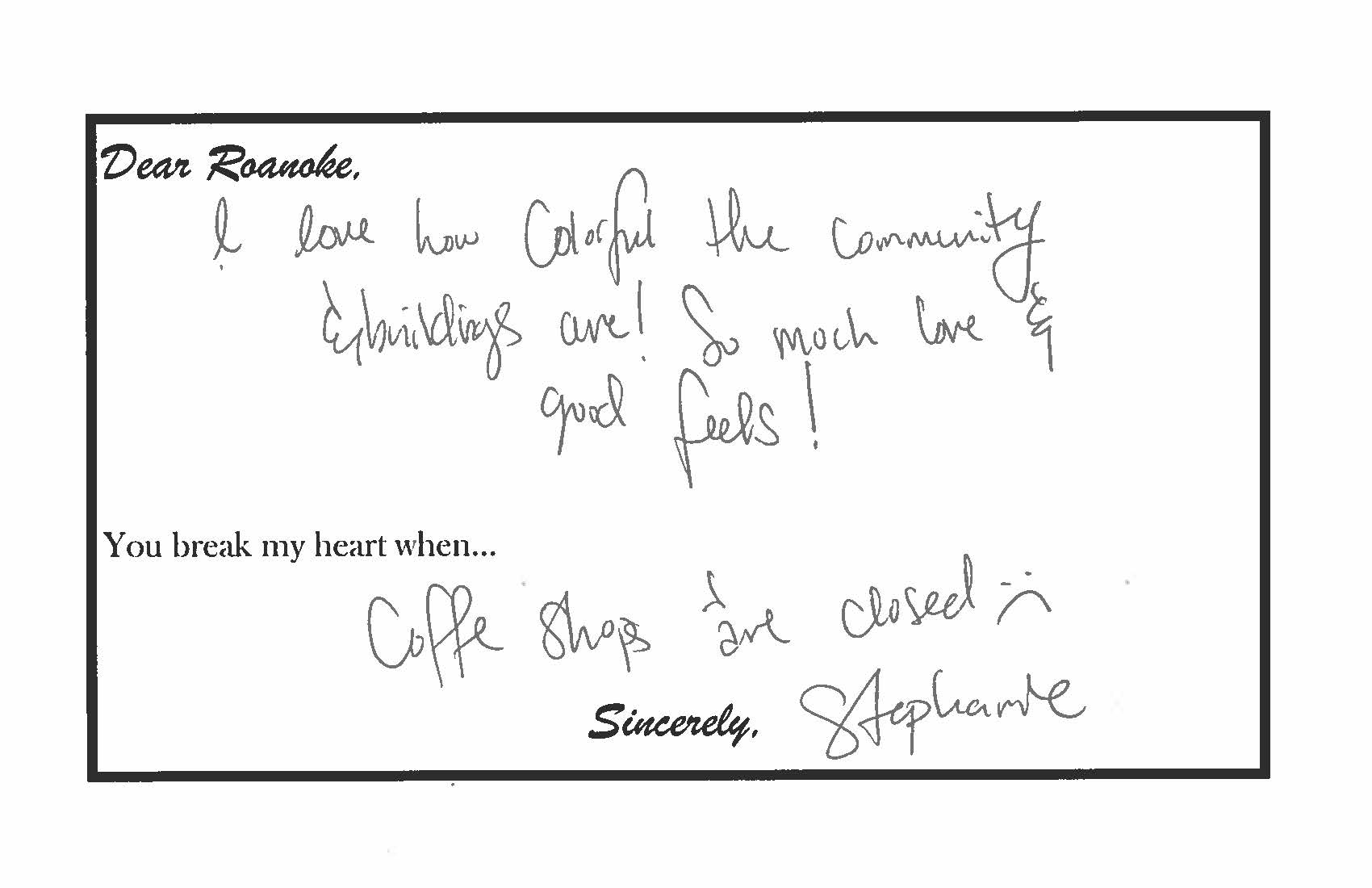

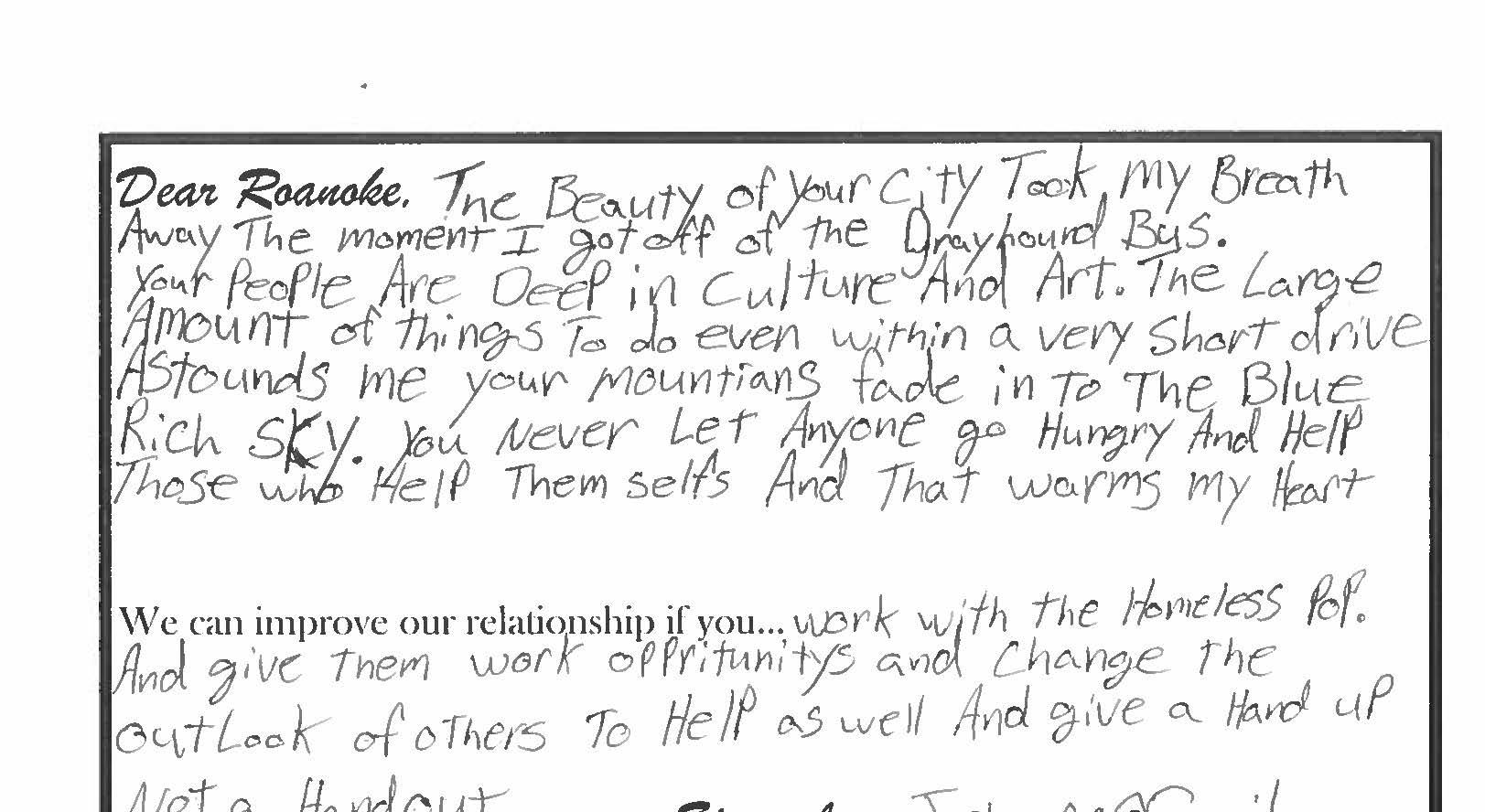

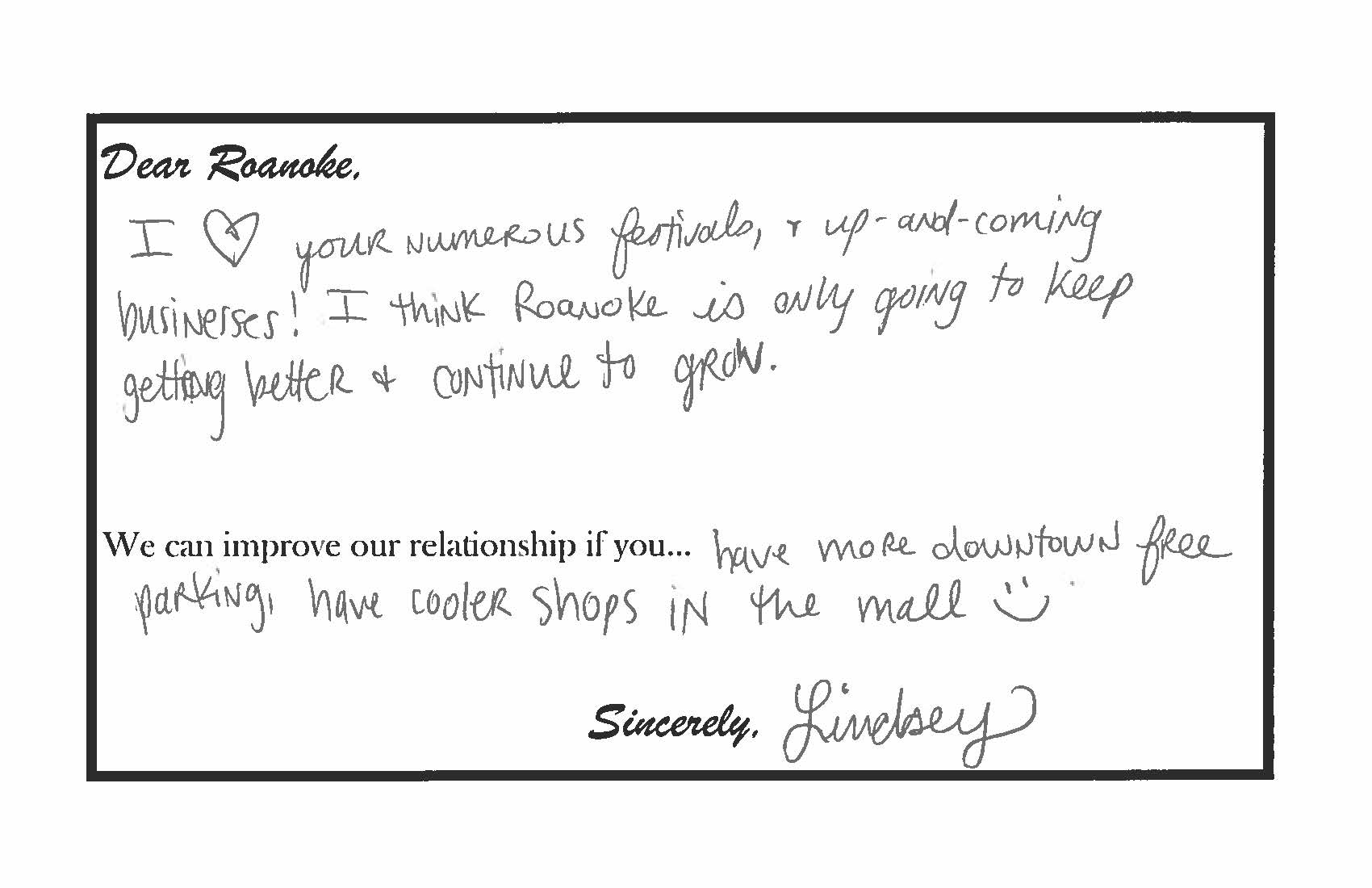

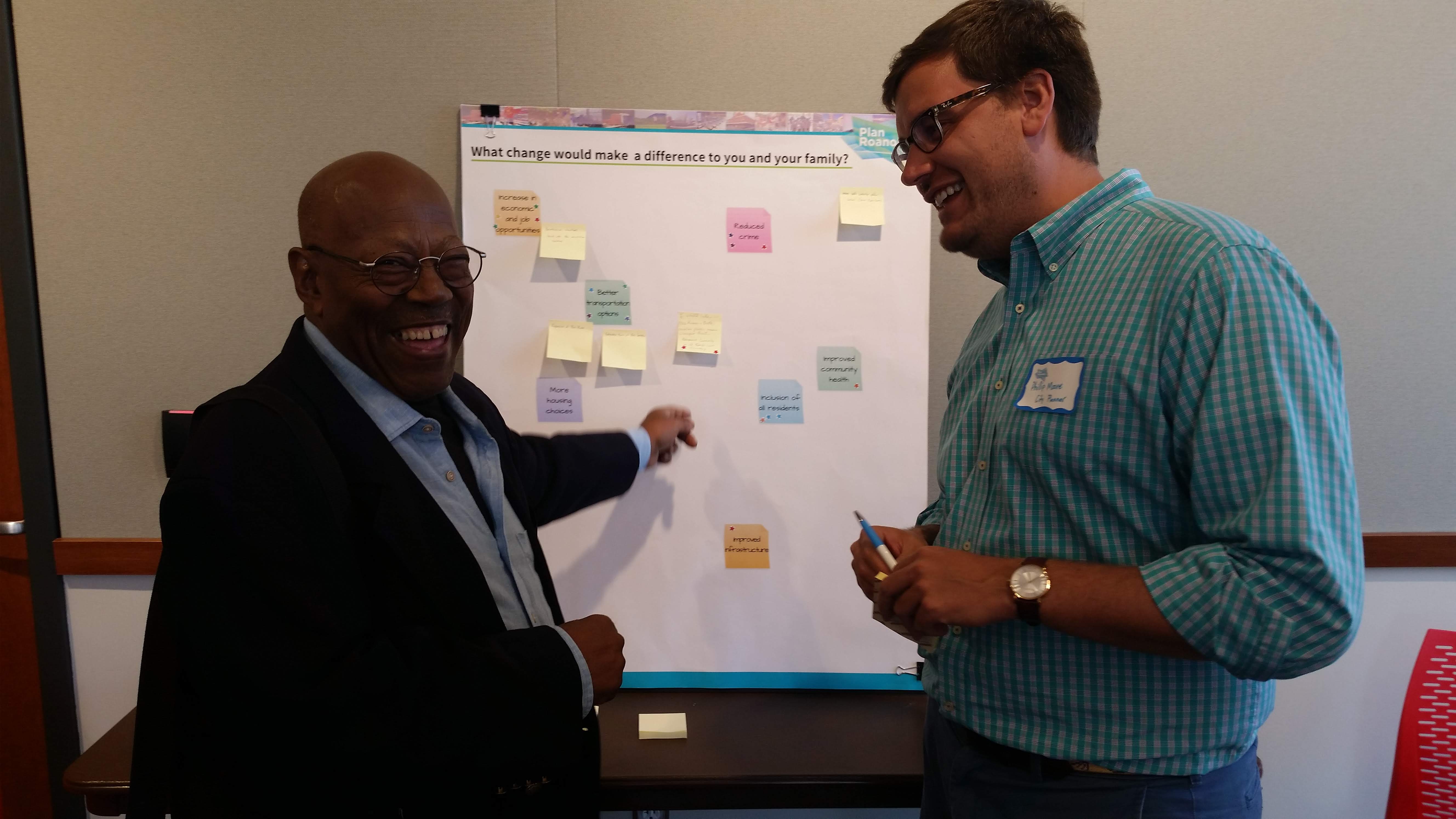

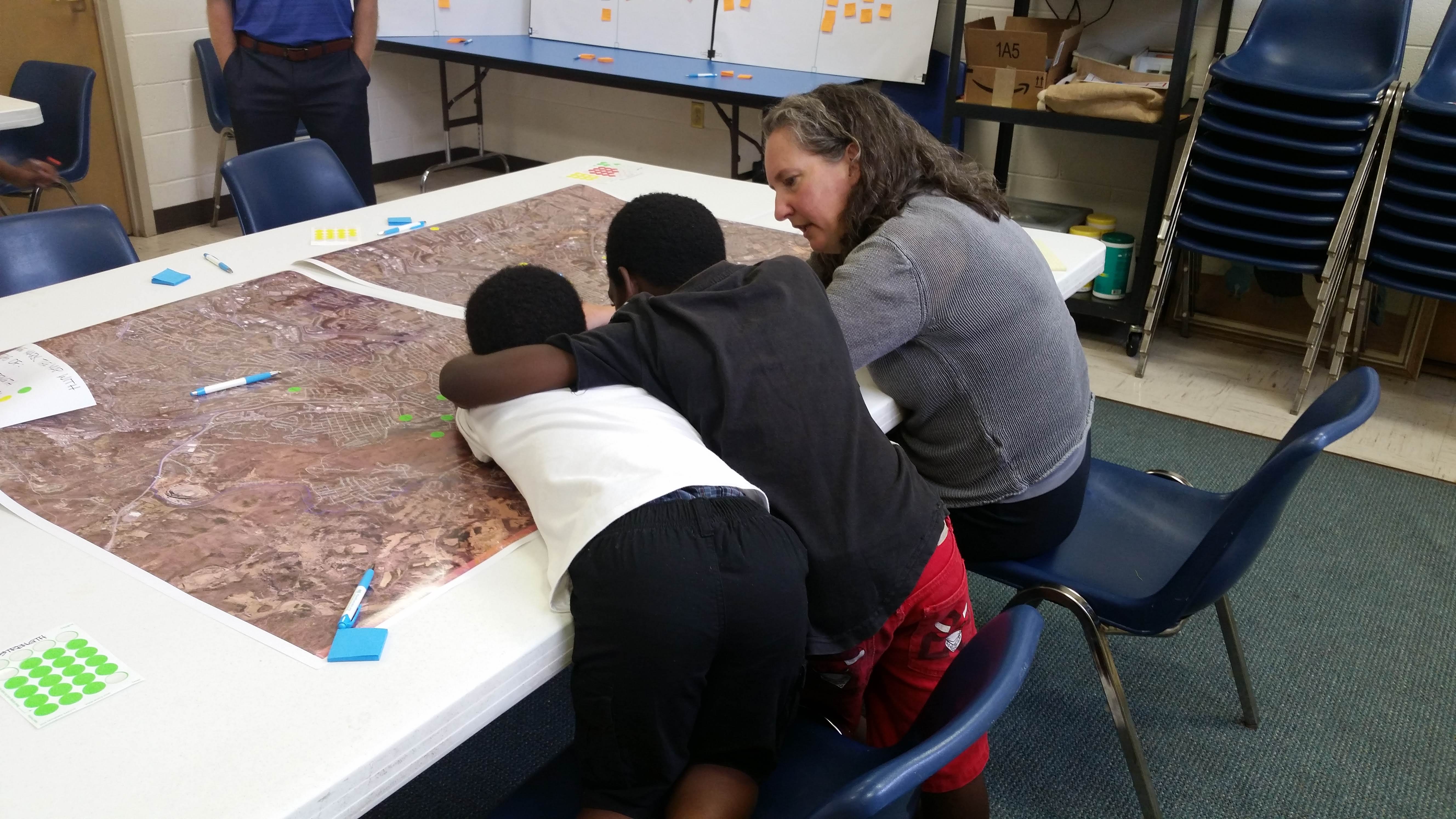

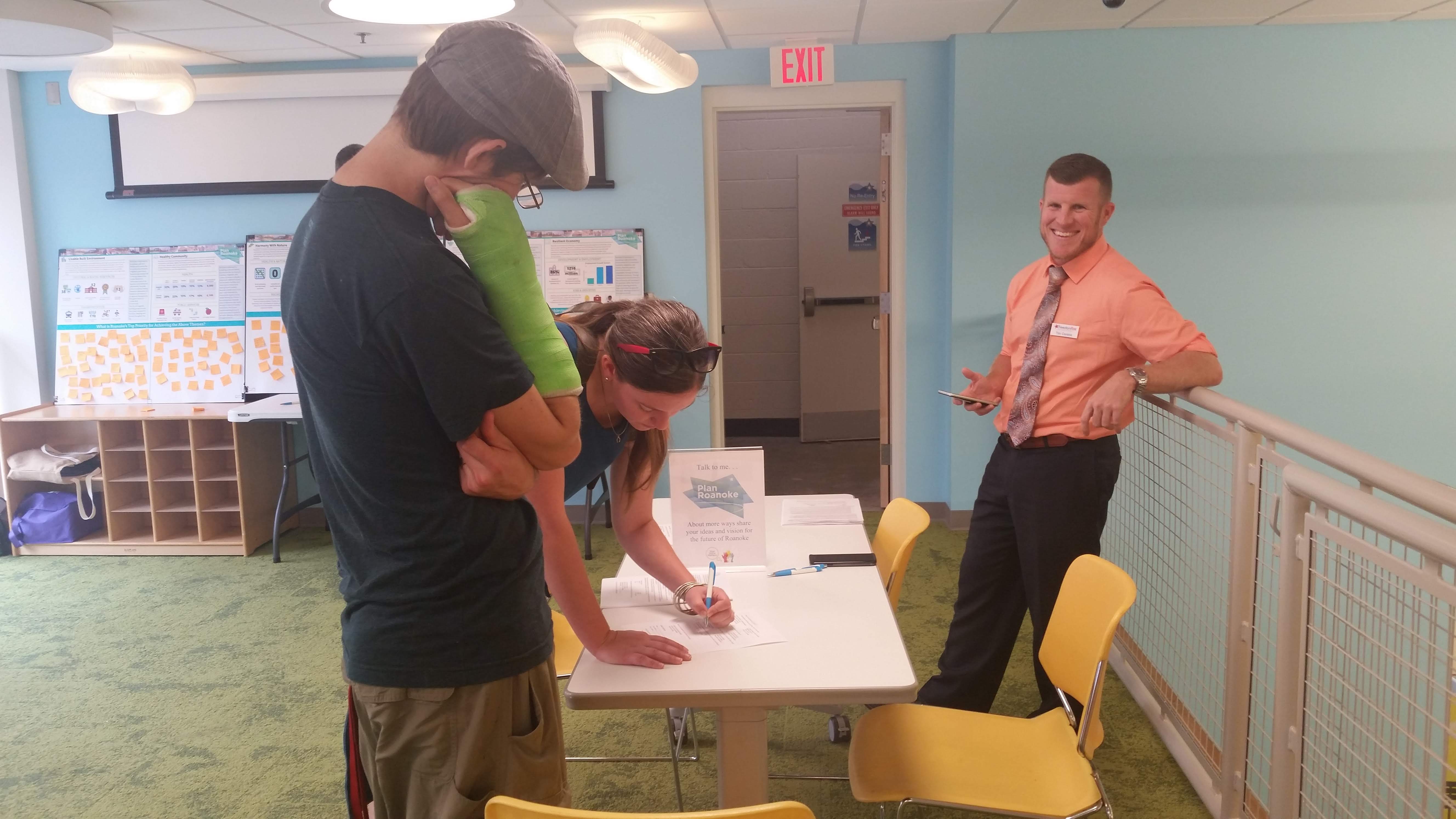

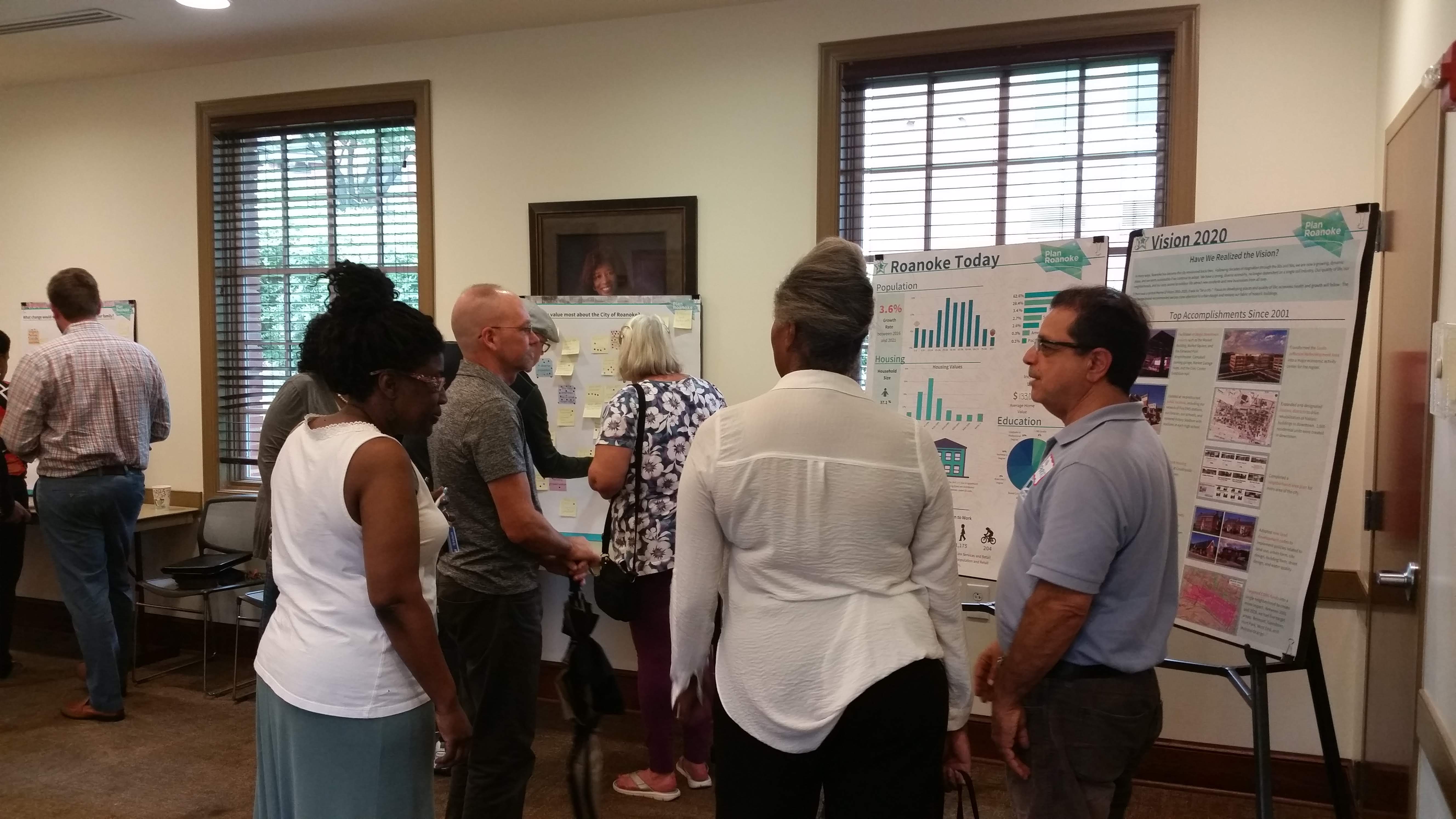

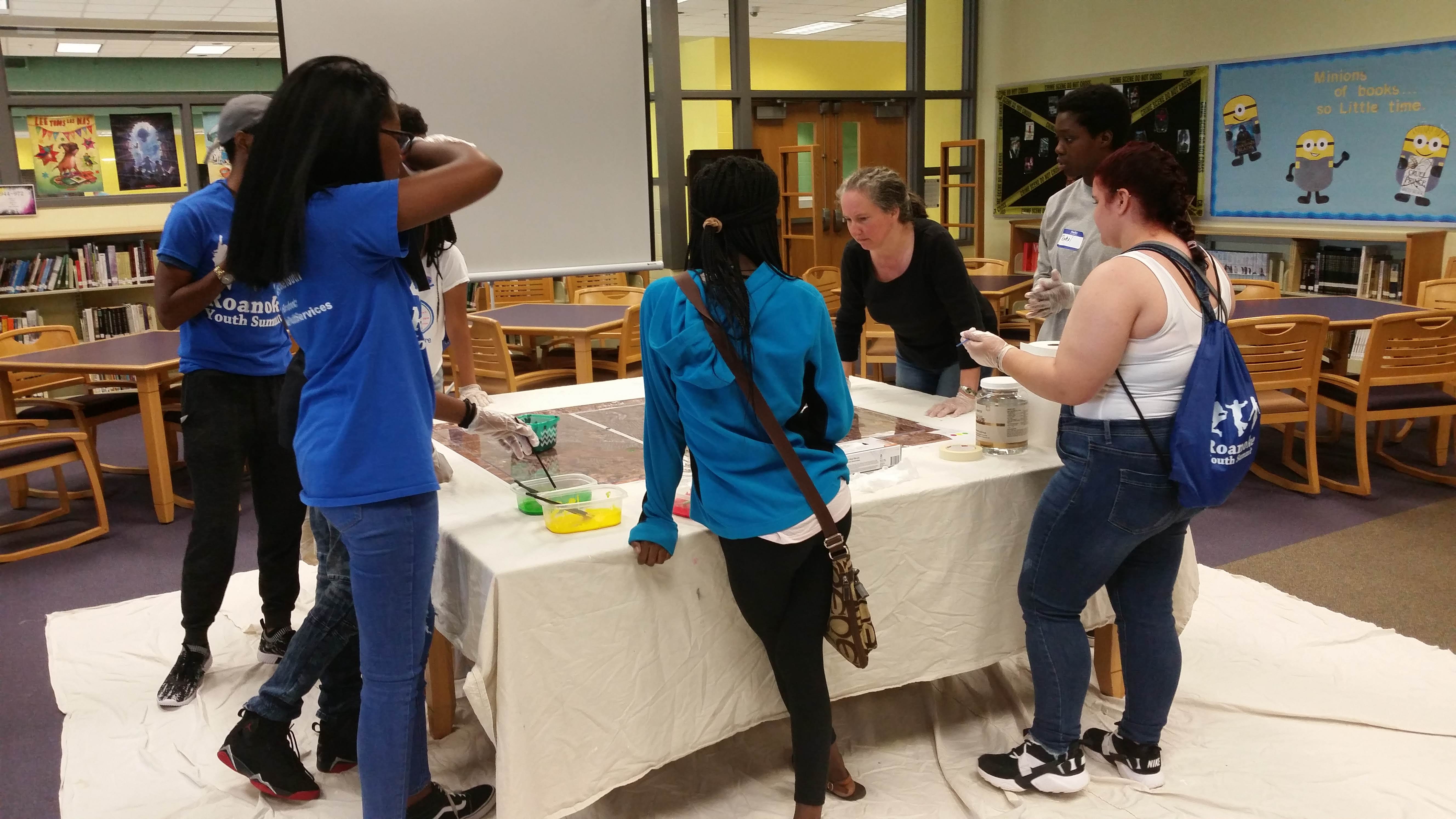

The most important step in any planning process involves collaborating with members of the community. Without listening and gaining an understanding of community needs and values, it is impossible to develop a meaningful plan.

Authentic participation requires not only meaningful involvement with citizens throughout the planning process, but the empowerment of citizens to become driving forces within their own communities. To “ensure that the planning process actively involves all segments of the community in analyzing issues, generating vision, developing plans, and monitoring outcomes”, the American Planning Association identifies seven actions in their Best Practices for Comprehensive Plans. These include:

- Engage stakeholders at all stages of the planning process.

- Seek diverse participation in the planning process.

- Promote leadership development in disadvantaged communities through the planning process.

- Develop alternative scenarios of the future.

- Provide ongoing and understandable information for all participants.

- Use a variety of communications channels to inform and involve the community.

- Continue to engage the public after the comprehensive plan is adopted.

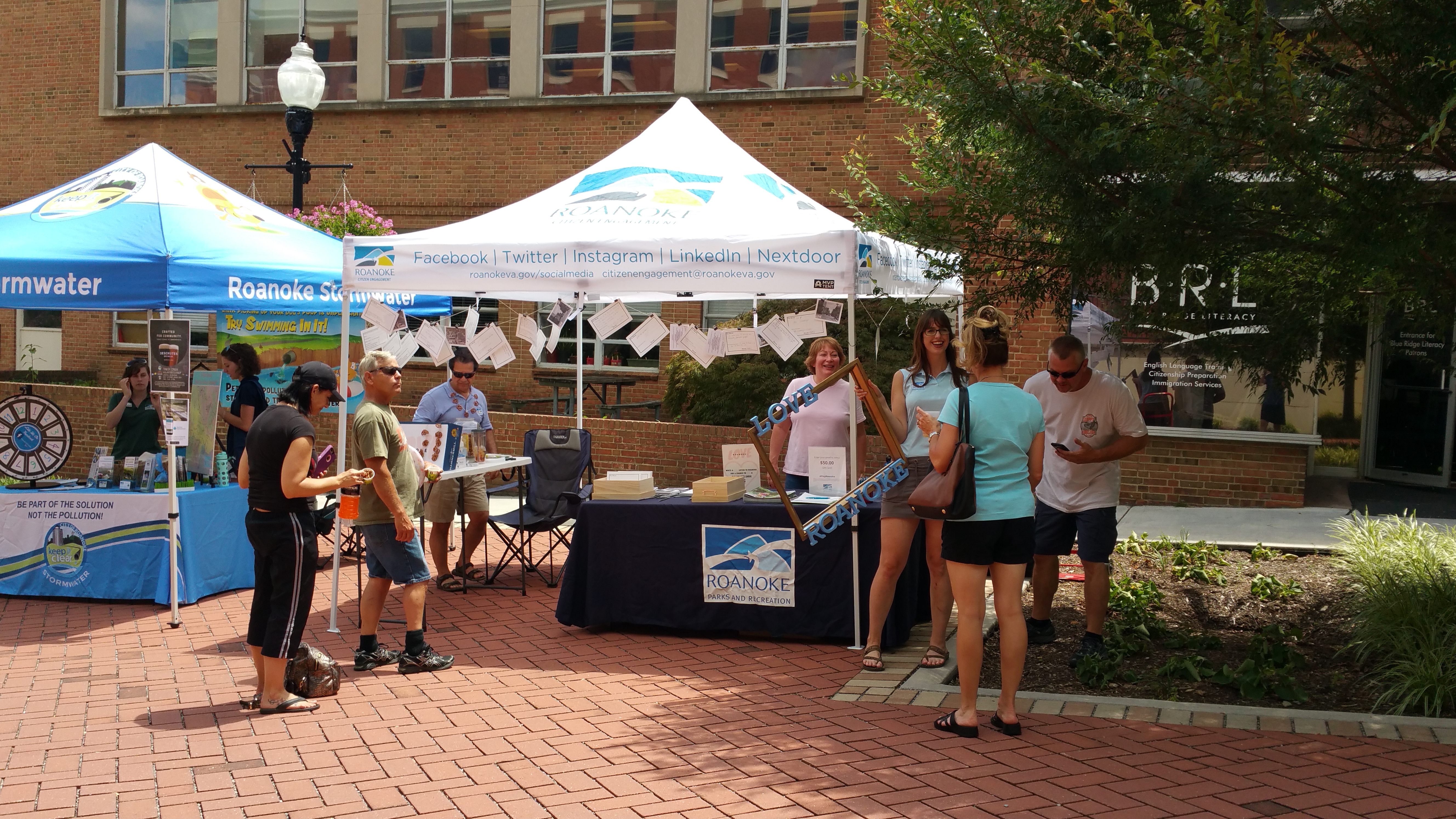

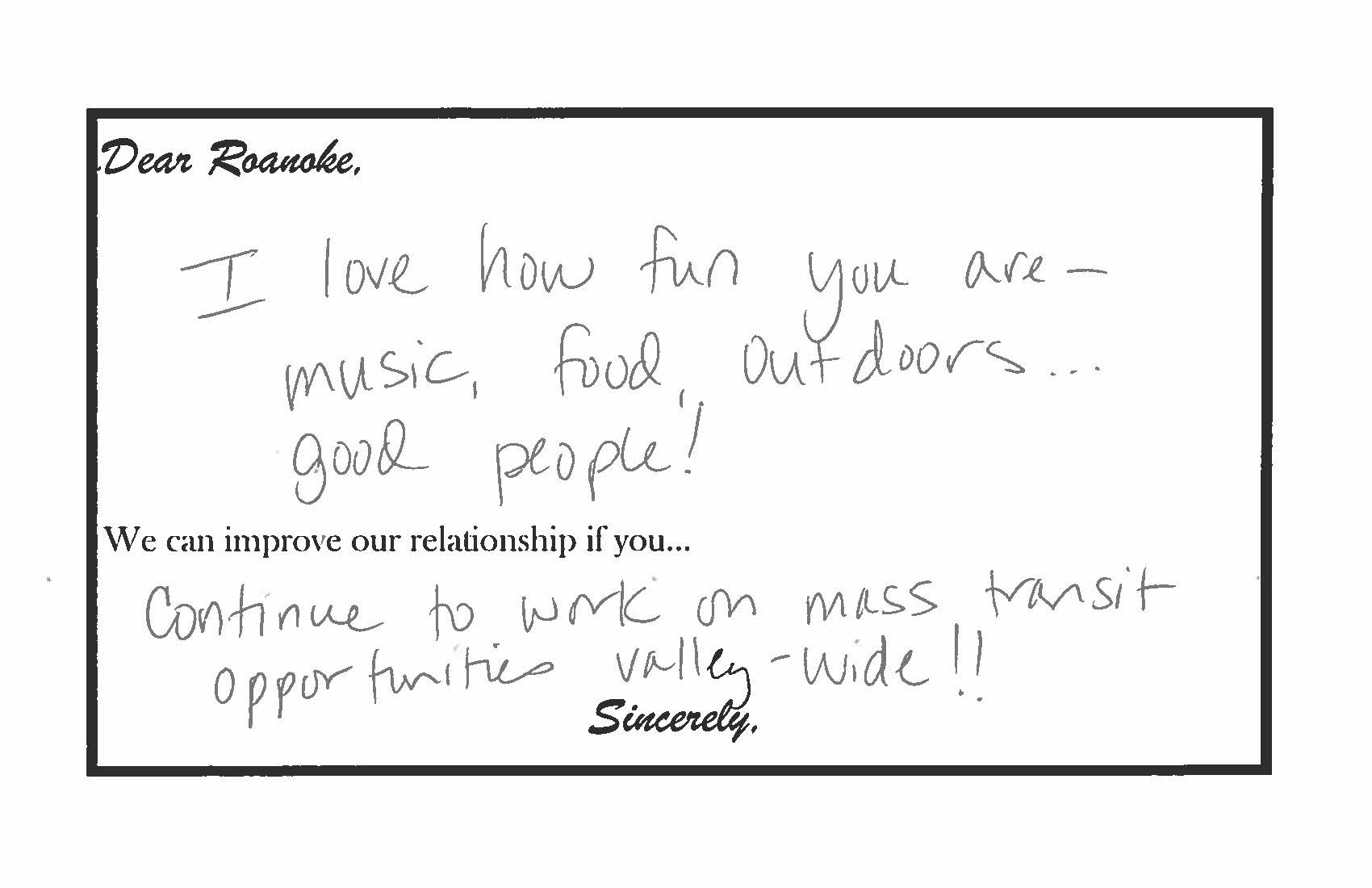

To achieve the seven recommended actions, citizens and stakeholders were engaged throughout plan development. Varying outreach methods were used to contact all communities within Roanoke in an effort to reach diverse participants. Planning staff relied on those already engaged to act as representatives and recruit others from their community into the planning process. Specific meetings were held to address equity and hard-to-reach areas. Updated information was continually provided in the form of reports, speakers, and events throughout the creation of City Plan 2040 to help residents create their vision for the City’s future.

Into the Future

Authentic participation will continually be an essential element in the planning process. City planners cannot plan for the community without knowing what the community wants and needs. To improve engagement and empower citizens, City Plan 2040 recommends several measures to create new, community represented commissions and groups to ensure equity and public oversight in future decision-making. Additionally, the Plan will be revisited every five years by planners and citizens in order to ensure accountability and track progress.

Several plans are recommended as part of City Plan 2040 with a focus on equity and integration. These plans, along with specialized Neighborhood Plans, will accompany and expand on the goals of the comprehensive plan. Each of these plans will involve a vigorous public component, relying on community leaders and organizations to achieve maximum public participation.

In order to build capacity for the public to participate in planning and other civic processes, the City is working to increase educational opportunities. Courses like Roanoke’s Leadership College, Planning Academy, and Green Academy aim to provide citizens with the tools and knowledge to navigate public processes and use them for community empowerment.

City Plan 2040 broadly covers a wide range of topics to help us reach our community goals and aspirations. To identify these goals we worked through an intensive public engagement process and then established community working groups to identify priorities, policies and actions in each of the City Plan 2040 theme areas.

We learned from the working group process that there are eight big ideas that need to be developed and addressed in City Plan 2040. These can be broken into three categories. We also identified two big ideas for how we can improve the way the city conducts its business.

There is much work to be accomplished over the next 20 years to advance these big ideas. Important priorities, policies and actions are identified in City Plan 2040 to move these big ideas forward and to transform Roanoke. Working together as a community we can make that transformation happen.

City Plan 2040 is guided by six themes drawn from the American Planning Association’s (APA) Best Practices for Comprehensive Plans. The APA identified six principles necessary to ensure a sustainable community. This plan extends those principles into themes that target pressing community concerns, while anticipating Roanoke’s future needs. These themes will ensure a holistic planning approach that addresses environmental, social, and economic well-being.

Each theme consists of priorities, policies, and actions. The plan’s priorities are the most prominent areas of concern identified by the community. The plan’s policies create a decision-making guide to address each priority. The plan’s actions are specific steps needed to implement each policy and achieve the long-term vision of City Plan 2040.

City Plan 2040 has developed policies and actions to achieve a shared vision built around six themes recognized by the American Planning as necessary to ensure a sustainable community. The plan also evaluated the history of land use, transportation, and urban design and their effects on the patterns of development and existing land uses. In reviewing these elements of city design, additional policies have been created to help guide future decision making and investment. City Plan 2040 recognizes the need to be intentional about the design and development of the city to be successful in building a sustainable community and achieving the community priorities established in the plan.

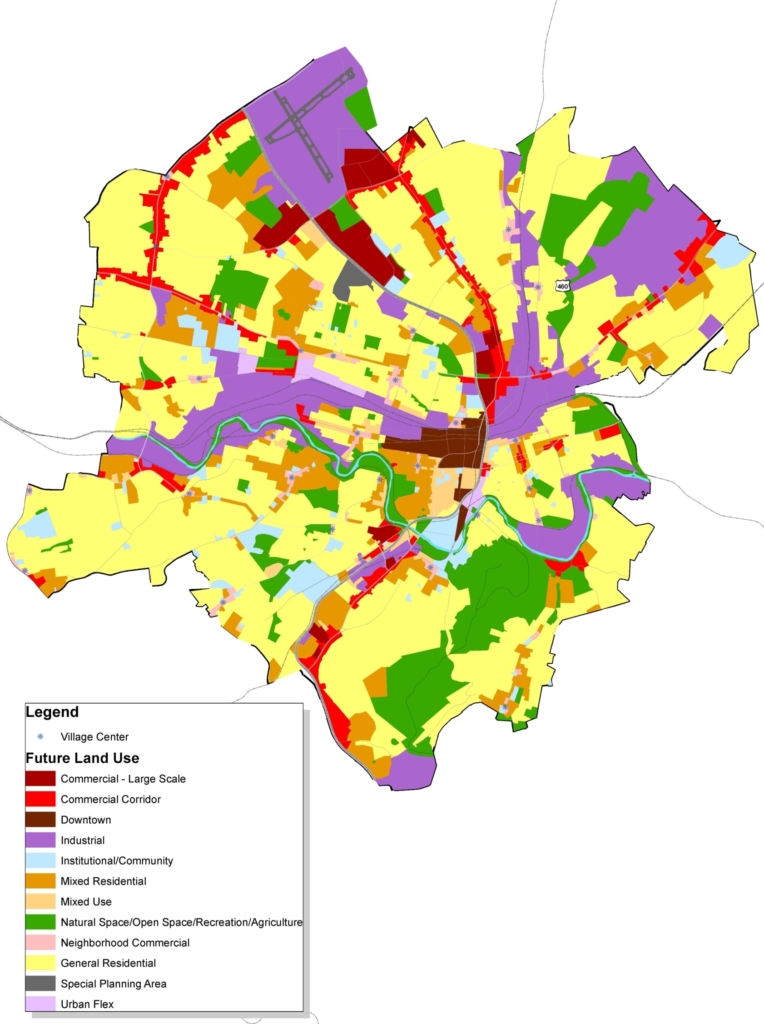

The future land use element of this plan identifies twelve general categories of activities that are carried out within the City. This element also contains a map of future land use designations that incorporates the land use mapping of neighborhood and area plans. Neighborhood and area plans are the vehicle for studying land use in detail, down to each individual property. Subsequent neighborhood plans will use these designations for consistency. Each neighborhood is unique, with its own development patterns and needs, so neighborhood and area plans will address how these broad categories apply in those contexts.

Land Use Categories

- General Residential

- Mixed Residential

- Mixed Use

- Neighborhood Commercial

- Commercial Corridor

- Downtown

- Large Center

- Institutional and Community

- Natural Areas, Open Space, Recreation

- Industrial-Commercial Flex

- Industrial

- Special Planning Area

Implementing the Land Use Plan

The principal tool for implementing the land use plan is the zoning code. The zoning code consists of two parts that work hand-in-hand: one is a set of written regulations and the other is a map that designates zoning districts throughout the City. No immediate changes to the City’s zoning map are proposed as part of this broad land use plan. As neighborhood and area plans are developed it is expected that strategic map changes could be made to implement those plans.

General policy changes recommended by this plan, such as requirements for site development and how certain land uses are regulated, are implemented through changes in the text of the zoning code. The zoning code is updated fairly frequently—18 times in 15 years—to reflect evolving ideas and needs. Conceptually, planning staff seeks to provide just enough guidance to produce desired results of compatibility and good urban design. Amendments usually remove unnecessary or ineffective regulations in order to make it easier to develop sites or start a business. Indeed, through constant improvements, the zoning code is simpler and more streamlined in 2020 than it was in 2005. Other code changes will be made to address needs identified in special topic plans, such as housing studies, or economic development plans, or other observed development trends or community needs that need to be addressed.

Land Use Categories Described

City Planning Framework

Like most states, Virginia mandates that each locality adopt a 20 year comprehensive plan. Typically conceived as a single document, the Code of Virginia spells out what comprehensive plans are required to address. Given the complexities of a city, an ongoing program of city planning is needed to support development of meaningful policies that focus on specific topics like parks or focus on the needs of each community. Moreover, multiple plans are needed to address the full range of issues while properly engaging communities in the planning process.

Roanoke has a framework where many plans are adopted as components of the comprehensive plan. Vision 2001-2020 served as “umbrella” plan for all other planning documents. Despite being one of many documents, Vision 2001-2020 was generically referred to as the comprehensive plan.

Since Vision 2001-2020 was adopted, over 40 other plans were adopted as components of the comprehensive plan. Functional plans focus on specific civic infrastructure or specific aspects of community development. As of the date of this plan, 14 plans were adopted as functional components of the comprehensive plan. Community Plans that focus on different geographic areas have been adopted for every part of the city. As of 2020, 27 plans have been adopted as place-based components. These plans will be carried forward with this plan and will be updated as needed.

Going forward, Roanoke should employ a framework of three volumes that comprise the comprehensive plan, with Volume I as the overall comprehensive plan document, Volume II as the body of functional plans, and Volume III as the collection of community plans.

City Plan 2040 – the Volume I General Plan – is oriented toward broad policy with some strategies and actions suggested. Volume II and III plans are more strategic in that they should interpret how broad principles and general policies are implemented at the functional and neighborhood levels.

On the heels of adopting this plan, there is a need to start updating the Volume II and Volume III components with a goal of completing updates by 2030.

The following plans will be carried forward with the adoption of City Plan 2040:

Volume II- Functional Plans

- Arts and Cultural Plan (2011)

- Citywide Brownfield Redevelopment Plan (2008)

- Downtown Roanoke 2017 (2017)

- Parks and Recreation Master Plan (2019)

- Roanoke Valley Conceptual Greenway Plan (2018)

- Urban Forestry Plan (2003)

- Wireless Telecommunication Policy (2016)

Volume III- Community Plans

- Belmont-Fallon Neighborhood Plan (2003)

- Countryside Master Plan (2011)

- Evans Spring Area Plan (2012)

- Fairland/Villa Heights Neighborhood Plan (2005)

- Franklin Road/Colonial Avenue Area Plan (2004)

- Gainsboro Neighborhood Plan (2003)

- Garden City Neighborhood Plan (2005)

- Gilmer Neighborhood Plan (2004)

- Grandin Court Neighborhood Plan (2005)

- Greater Deyerle Neighborhood Plan (2006)

- Greater Raleigh Court Neighborhood Plan (2007)

- Harrison & Washington Park Neighborhood Plan (2003)

- Hollins/Wildwood Area Plan (2005)

- Hurt Park/Mountain View/West End Neighborhood Plan (2003)

- Loudon-Melrose/Shenandoah West Neighborhood Plan (2010)

- Melrose-Rugby Neighborhood Plan (2010)

- Mill Mountain Park Management Plan (2006)

- Morningside/Kenwood/Riverdale Neighborhood Plan (2003)

- Mountain View/Norwich Corridor Plan (2008)

- Norwich Neighborhood Plan (2003)

- Old Southwest Neighborhood Plan (2009)

- Peters Creek North Neighborhood Plan (2002)

- Peters Creek South Neighborhood Plan (2005)

- Riverland/Walnut Hill Neighborhood Plan (2004)

- South Jefferson Redevelopment Area (2012)

- South Roanoke Neighborhood Plan (2008)

- Southern Hills Neighborhood Plan (2002)

- Wasena Neighborhood Plan (2003)

- Williamson Road Area Plan (2004)

Vision

City Plan 2040 is a comprehensive plan that will guide investment and decision-making in Roanoke over the next 20 years. The plan recommends policies and actions that work together to achieve the following vision.

In 2040, Roanoke will be:

- A city that considers equity in each of its policies and provides opportunity for all, regardless of background.

- A city that ensures the health and safety of every community member.

- A city that understands its natural assets and prioritizes sustainable innovation.

- A city that interweaves design, services, and amenities to provide high livability.

- A city that collaborates with its neighbors to improve regional quality of life.

- A city that promotes sustainable growth through targeted development of industry, business, and workforce.

Themes

City Plan 2040 is guided by six themes drawn from the American Planning Association’s (APA) Best Practices for Comprehensive Plans.The APA identified six principles necessary to ensure a sustainable community. This plan extends those principles into themes that target pressing community concerns, while anticipating Roanoke’s future needs. These themes will ensure a holistic planning approach that addresses environmental, social, and economic well-being. The following six themes will inform the elements of the plan.

- Interwoven Equity

- Healthy Community

- Harmony with Nature

- Livable Built Environment

- Responsible Regionalism

- Resilient Economy

Elements

The elements of City Plan 2040 consist of priorities, policies, and actions. The plan’s priorities are the most prominent areas of concern identified by the community. The plan’s policies create a decision-making guide to address each priority. The plan’s actions are specific steps needed to implement each policy and achieve the long-term vision of City Plan 2040.

Population

Roanoke’s population has remained relatively stable over the past 60 years. It hasn’t fluctuated more than 10 percent above or below an average of 96,747 during those decades.

Much of Roanoke’s post WWII population gains were the result of annexation of adjacent growth areas. City annexations ended in the mid-1970s when a statewide moratorium was enacted. Roanoke’ population numbers began to decline, falling from a peak just over 105,000 and bottoming out around 92,000. It appeared people might be fleeing the city, but the number of housing units continued to increase; 14,000 net new housing units were created between 1970 and 2010. What was actually happening was that households were getting much smaller. A massive drop in housing density was occurring as the household sizes fell from 2.7 people per household to just 2.0.

Roanoke’s Population and Housing Units

With the increasing attraction of urban living, decades of population decline have ended and Roanoke is seeing modest population increases. According to the University of Virginia’s Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service, Roanoke City’s population is estimated to have just surpassed 100,000 in 2019 and is expected to continue to increase to more than 105,000 in 2040. Roanoke’s population has been growing at a rate of 6.5% since 2009, a rate that is lower than Virginia’s (7.6%) but higher than the national growth rate (5.6%).

Median age for Roanoke is 38.1 years, slightly higher than that of Virginia and the United States but no so high as to cause concern. A high median age can indicate in-migration of seniors or outmigration of young people. Roanoke’s age distribution creates bell-shaped curve, which indicates a normal age structure.

Looking at age brackets over time, one can see changes each year. Again, most of the profile for Roanoke is stable with the exception of the 64-74 bracket which show increases as the Baby Boomers’s cohort moves through. Also notable is the upward trend in the 5-14 age bracket and the downward trend of the 15-24 bracket. However, both changes are relatively slight.

Population by Race

Roanoke’s population is predominantly white (64%) and African American (29%). While still a relatively small population in absolute numbers, the Hispanic population is increasing in terms of growth rates. Considering that People of Color make up over a third of our population, an understanding of our racial and ethnic composition is important to ideas about interwoven equity and inclusion.

Household Size

The average household size for both owner-occupied and renter-occupied Roanoke residents is 2.28 which has increased since 2010. The majority of households have two or fewer people. Single person households account for 37.1% of households and two-person households account for 32.3% of households.

Household Income and Affordability

Roanoke’s median household income of $53,000 is considerably lower than that of Virginia ($90,000) and the United States ($78,000). Housing costs are also considerably lower: the median home value is $133,000 and the median rent is $748 while the median value for Virginia is $248,000 and median rent is $1,135.

Discussions about affordable housing often lead to the question of ‘Affordable for whom?’ Regional variation in incomes and housing costs can be accounted for when determining affordability by assessing how many and to what extent households are cost burdened by their housing expenses. Cost burdened is defined as spending more than 30% of household income on housing.

Despite Roanoke’s very low housing costs relative to Virginia and the US, we still have a considerable issue with households being cost burdened. The map shows the percentage of households that are cost burdened in each census tract. Darker colors indicate more households are cost burdened. In each year since 2008, more than a third of Roanoke’s households have been cost burdened by monthly mortgage payments or rent. For more details on measuring housing affordability, check out Housing Forward Virginia’s Sourcebook.

Commuting

About 47,000 people commute into Roanoke every day for work and the overwhelming majority use cars as their mode of transportation. Less than ten percent use a different mode of transportation such as biking, walking, or transit. The mean travel time for inbound commuters is 20 minutes, which is lower than that of Virginia at 28 minutes and the United States at 26 minutes.

Upward Mobility

Upward mobility is a persons’ ability to move up in economic status regardless of the economic status they were born into. Cities are beginning to analyze the factors that affect upward mobility as a strategy to address poverty. Segregation by income and race is an important factor in determining a cities degree of upward mobility. The map below shows the median household income in 2016 by census tract. Lower incomes, represented by lighter shades, are concentrated in one area of the city.

The Opportunity Atlas, a collaboration of researchers from the Census Bureau, Harvard, and Brown, enables anyone to explore the details of economic mobility in Roanoke (and beyond).

The map below shows the concentration of white and black populations by census tract. Comparing these maps allows us to see the segregation by income and race for Roanoke.

Studies have shown that two parent households are also an important factor when determining upward mobility. The map below shows the share of single parent households by census tract. The same areas that show lower incomes also have the largest share of single parent households. Upward mobility has been an issue that has been identified by various groups in Roanoke. It is important that issues such as upward mobility are recognized and addressed as the city plans for the next twenty years.

All information: U.S. Census Bureau, ACS 5 year estimate, 2016, Factfinder.census.gov

The most important step in any planning process involves collaborating with members of the community. Without listening and gaining an understanding of community needs and values, it is impossible to develop a meaningful plan.

Authentic participation requires not only meaningful involvement with citizens throughout the planning process, but the empowerment of citizens to become driving forces within their own communities. To “ensure that the planning process actively involves all segments of the community in analyzing issues, generating vision, developing plans, and monitoring outcomes”, the American Planning Association identifies seven actions in their Best Practices for Comprehensive Plans. These include:

- Engage stakeholders at all stages of the planning process.

- Seek diverse participation in the planning process.

- Promote leadership development in disadvantaged communities through the planning process.

- Develop alternative scenarios of the future.

- Provide ongoing and understandable information for all participants.

- Use a variety of communications channels to inform and involve the community.

- Continue to engage the public after the comprehensive plan is adopted.

To achieve the seven recommended actions, citizens and stakeholders were engaged throughout plan development. Varying outreach methods were used to contact all communities within Roanoke in an effort to reach diverse participants. Planning staff relied on those already engaged to act as representatives and recruit others from their community into the planning process. Specific meetings were held to address equity and hard-to-reach areas. Updated information was continually provided in the form of reports, speakers, and events throughout the creation of City Plan 2040 to help residents create their vision for the City’s future.

Into the Future

Authentic participation will continually be an essential element in the planning process. City planners cannot plan for the community without knowing what the community wants and needs. To improve engagement and empower citizens, City Plan 2040 recommends several measures to create new, community represented commissions and groups to ensure equity and public oversight in future decision-making. Additionally, the Plan will be revisited every five years by planners and citizens in order to ensure accountability and track progress.

Several plans are recommended as part of City Plan 2040 with a focus on equity and integration. These plans, along with specialized Neighborhood Plans, will accompany and expand on the goals of the comprehensive plan. Each of these plans will involve a vigorous public component, relying on community leaders and organizations to achieve maximum public participation.

In order to build capacity for the public to participate in planning and other civic processes, the City is working to increase educational opportunities. Courses like Roanoke’s Leadership College, Planning Academy, and Green Academy aim to provide citizens with the tools and knowledge to navigate public processes and use them for community empowerment.

City Plan 2040 broadly covers a wide range of topics to help us reach our community goals and aspirations. To identify these goals we worked through an intensive public engagement process and then established community working groups to identify priorities, policies and actions in each of the City Plan 2040 theme areas.

We learned from the working group process that there are eight big ideas that need to be developed and addressed in City Plan 2040. These can be broken into three categories. We also identified two big ideas for how we can improve the way the city conducts its business.

There is much work to be accomplished over the next 20 years to advance these big ideas. Important priorities, policies and actions are identified in City Plan 2040 to move these big ideas forward and to transform Roanoke. Working together as a community we can make that transformation happen.

City Plan 2040 is guided by six themes drawn from the American Planning Association’s (APA) Best Practices for Comprehensive Plans. The APA identified six principles necessary to ensure a sustainable community. This plan extends those principles into themes that target pressing community concerns, while anticipating Roanoke’s future needs. These themes will ensure a holistic planning approach that addresses environmental, social, and economic well-being.

Each theme consists of priorities, policies, and actions. The plan’s priorities are the most prominent areas of concern identified by the community. The plan’s policies create a decision-making guide to address each priority. The plan’s actions are specific steps needed to implement each policy and achieve the long-term vision of City Plan 2040.

City Plan 2040 has developed policies and actions to achieve a shared vision built around six themes recognized by the American Planning as necessary to ensure a sustainable community. The plan also evaluated the history of land use, transportation, and urban design and their effects on the patterns of development and existing land uses. In reviewing these elements of city design, additional policies have been created to help guide future decision making and investment. City Plan 2040 recognizes the need to be intentional about the design and development of the city to be successful in building a sustainable community and achieving the community priorities established in the plan.

The future land use element of this plan identifies twelve general categories of activities that are carried out within the City. This element also contains a map of future land use designations that incorporates the land use mapping of neighborhood and area plans. Neighborhood and area plans are the vehicle for studying land use in detail, down to each individual property. Subsequent neighborhood plans will use these designations for consistency. Each neighborhood is unique, with its own development patterns and needs, so neighborhood and area plans will address how these broad categories apply in those contexts.

Land Use Categories

- General Residential

- Mixed Residential

- Mixed Use

- Neighborhood Commercial

- Commercial Corridor

- Downtown

- Large Center

- Institutional and Community

- Natural Areas, Open Space, Recreation

- Industrial-Commercial Flex

- Industrial

- Special Planning Area

Implementing the Land Use Plan

The principal tool for implementing the land use plan is the zoning code. The zoning code consists of two parts that work hand-in-hand: one is a set of written regulations and the other is a map that designates zoning districts throughout the City. No immediate changes to the City’s zoning map are proposed as part of this broad land use plan. As neighborhood and area plans are developed it is expected that strategic map changes could be made to implement those plans.

General policy changes recommended by this plan, such as requirements for site development and how certain land uses are regulated, are implemented through changes in the text of the zoning code. The zoning code is updated fairly frequently—18 times in 15 years—to reflect evolving ideas and needs. Conceptually, planning staff seeks to provide just enough guidance to produce desired results of compatibility and good urban design. Amendments usually remove unnecessary or ineffective regulations in order to make it easier to develop sites or start a business. Indeed, through constant improvements, the zoning code is simpler and more streamlined in 2020 than it was in 2005. Other code changes will be made to address needs identified in special topic plans, such as housing studies, or economic development plans, or other observed development trends or community needs that need to be addressed.

Land Use Categories Described

City Planning Framework

Like most states, Virginia mandates that each locality adopt a 20 year comprehensive plan. Typically conceived as a single document, the Code of Virginia spells out what comprehensive plans are required to address. Given the complexities of a city, an ongoing program of city planning is needed to support development of meaningful policies that focus on specific topics like parks or focus on the needs of each community. Moreover, multiple plans are needed to address the full range of issues while properly engaging communities in the planning process.

Roanoke has a framework where many plans are adopted as components of the comprehensive plan. Vision 2001-2020 served as “umbrella” plan for all other planning documents. Despite being one of many documents, Vision 2001-2020 was generically referred to as the comprehensive plan.

Since Vision 2001-2020 was adopted, over 40 other plans were adopted as components of the comprehensive plan. Functional plans focus on specific civic infrastructure or specific aspects of community development. As of the date of this plan, 14 plans were adopted as functional components of the comprehensive plan. Community Plans that focus on different geographic areas have been adopted for every part of the city. As of 2020, 27 plans have been adopted as place-based components. These plans will be carried forward with this plan and will be updated as needed.

Going forward, Roanoke should employ a framework of three volumes that comprise the comprehensive plan, with Volume I as the overall comprehensive plan document, Volume II as the body of functional plans, and Volume III as the collection of community plans.

City Plan 2040 – the Volume I General Plan – is oriented toward broad policy with some strategies and actions suggested. Volume II and III plans are more strategic in that they should interpret how broad principles and general policies are implemented at the functional and neighborhood levels.

On the heels of adopting this plan, there is a need to start updating the Volume II and Volume III components with a goal of completing updates by 2030.

The following plans will be carried forward with the adoption of City Plan 2040:

Volume II- Functional Plans

- Arts and Cultural Plan (2011)

- Citywide Brownfield Redevelopment Plan (2008)

- Downtown Roanoke 2017 (2017)

- Parks and Recreation Master Plan (2019)

- Roanoke Valley Conceptual Greenway Plan (2018)

- Urban Forestry Plan (2003)

- Wireless Telecommunication Policy (2016)

Volume III- Community Plans

- Belmont-Fallon Neighborhood Plan (2003)

- Countryside Master Plan (2011)

- Evans Spring Area Plan (2012)

- Fairland/Villa Heights Neighborhood Plan (2005)

- Franklin Road/Colonial Avenue Area Plan (2004)

- Gainsboro Neighborhood Plan (2003)

- Garden City Neighborhood Plan (2005)

- Gilmer Neighborhood Plan (2004)

- Grandin Court Neighborhood Plan (2005)

- Greater Deyerle Neighborhood Plan (2006)

- Greater Raleigh Court Neighborhood Plan (2007)

- Harrison & Washington Park Neighborhood Plan (2003)

- Hollins/Wildwood Area Plan (2005)

- Hurt Park/Mountain View/West End Neighborhood Plan (2003)

- Loudon-Melrose/Shenandoah West Neighborhood Plan (2010)

- Melrose-Rugby Neighborhood Plan (2010)

- Mill Mountain Park Management Plan (2006)

- Morningside/Kenwood/Riverdale Neighborhood Plan (2003)

- Mountain View/Norwich Corridor Plan (2008)

- Norwich Neighborhood Plan (2003)

- Old Southwest Neighborhood Plan (2009)

- Peters Creek North Neighborhood Plan (2002)

- Peters Creek South Neighborhood Plan (2005)

- Riverland/Walnut Hill Neighborhood Plan (2004)

- South Jefferson Redevelopment Area (2012)

- South Roanoke Neighborhood Plan (2008)

- Southern Hills Neighborhood Plan (2002)

- Wasena Neighborhood Plan (2003)

- Williamson Road Area Plan (2004)